Writing in braille was made easy by the Converto-Braille

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Sight is something that many of us take for granted. It’s unlikely that you’ll come across things written in braille all that often. Although braille is still relatively uncommon, there was a time when it’d be near impossible for people that were visually impaired to find reading material.

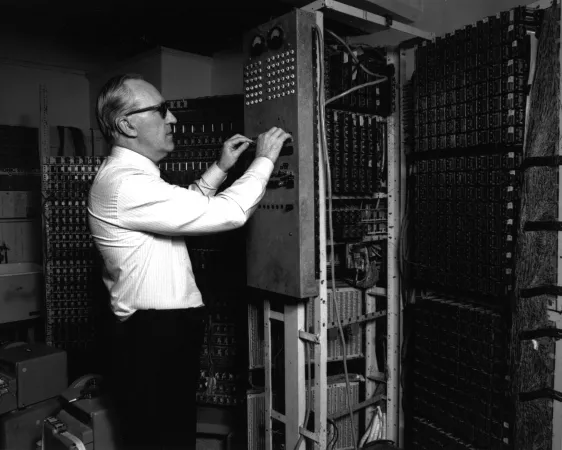

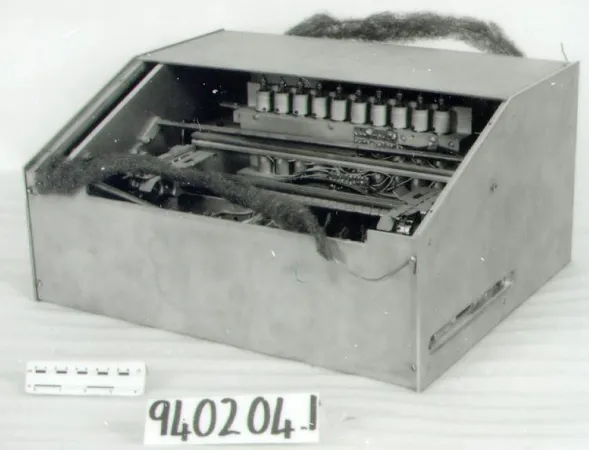

That was until the invention of the Converto-Braille, a braille printer designed by Roland Galarneau, a self-taught machinist from Hull, Quebec. Galarneau was visually impaired so he knew firsthand how little reading material was available in braille. He sought to fix this problem by creating a machine that allowed people to easily print text in braille without actually knowing how to read it.

In 1966 he created a computer-like device that would work as a normal typewriter to the naked eye, but functioned very differently under the hood. Every key struck would produce braille letters on the paper it printed. If the “A” key were to be tapped, an array of pins would shift and puncture the paper in a way to create the braille symbol for “A.” This allowed more people to transcribe existing reading material into braille despite knowing nothing about it.

As the Converto-Braille became more popular a blind woman in Montreal named Jeanne Cypihot wanted to help Galarneau. She aimed to fund his endeavors with 12 thousand dollars. Together they founded Converto-Braille Cypihot-Galarneau, a company that produced Galarneau’s projects and braille books. Later, the Canadian National Institute for the Blind and the Local Initiatives Program joined in financing them.

The company made all their devices with parts they had on hand and some parts donated by Bell. Twelve employees would operate Converto-Brailles and transcribe all sorts of texts into braille. In collaboration with the University of Ottawa, Converto-Braille Cypihot-Galarneau would also go on to record books on tape to compile the first French-language tape library in Canada.

With the evolution of technology, the Converto-Braille’s design moved towards modified IBM microcomputers in the 1980’s, capable of printing 720 braille pages an hour. Nowadays most of this can be done with software, but Galarneau’s contribution translated media for the visually impaired in a time when their options for literature were left in the dark.

By: Jassi Bedi