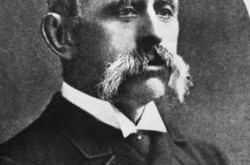

Thomas “Carbide” Wilson: Prolific Inventor and Father of Carbide

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Thomas “Carbide” Wilson was born in 1860 to a struggling farming family in Princeton, Upper Canada. When Thomas was 14, his father died, and his mother worked hard teaching guitar and painting lessons to put her children through school. Lucky for her, Thomas would soon become a prolific inventor and forever change the history of industry.

At the young age of 21, Thomas showed great intellectual promise by patenting electric arc lighting. As a result of his invention, in 1881, some shops and hotels in Hamilton displayed electric lights. They were the first electric lights most Hamiltonians ever saw.

Out of all of Wilson’s inventions, however, probably the one of the most important was his discovery of a way to produce calcium carbide.

Wilson discovered a cheap method of calcium carbide production via a twisting route of accidents and hard work. When travelling in the United States Thomas Wilson he met a man named Major James Turner. Major James Turner inspired in him an unshakable belief in the potential of the electric arc furnace. Wilson wanted to use the electric arc furnace to produce aluminum, a metal he believed would one day replace other metals on the market.

One of the major problems the duo encountered in producing aluminum was the lengthy amount of time taken for the furnace to cool down in order for the experiment’s needed sample to be taken. So, in order to reduce time and cost, Wilson decided to build a second unit that contained two furnaces so that one could cool while the other was in use. Wilson tried adding an assortment of metals and chemicals to the furnace in an attempt to produce aluminum, but had no success. His experiments were becoming costly, and his aluminum company was slowly going broke. Someone had suggested to Wilson to try producing metallic calcium before trying to produce aluminum, since they believed the metallic calcium could later be used to produce the desired aluminum.

In desperation, Wilson mixed coal tar and lime into the furnace hoping for the best. The mixture removed was dark and glutinous. Wilson, Turner, and their team were under the mistaken impression that they had produced metallic calcium. Later inspection by the leading scientist Lord Kelvin revealed the mixture was actually calcium carbide, otherwise known as acetylene.

At the time of their discovery, only six other people had seen calcium carbide. It was largely thought to be a scientific novelty- something rare but largely useless. With Wilson and Turner’s discovery, it now appeared that calcium carbide could be produced cheaply and quickly in large quantities. But, scientists wondered, what purpose would it have?

Metal welders began using acetylene to work with metal, but it was largely acetylene’s ability to produce a bright light that made it important for its first users. When it burned, the flame it produced was 12.5 times brighter than the flame of its rival, coal gas. Since Acetylene’s light contained all the colours of the spectrum, in proportions similar to natural light, it did not distort colours like other industrial light sources. Biologists discovered that fruits and vegetables ripened almost as quickly under acetylene light as they did in natural sunlight.

Within a few years of Wilson and Turner’s discovery, farmers were able to work in the cool of night, railway builders extended their hours, and lighthouses used acetylene to provide a brighter, more far-reaching light, for ships. Wilson and Turner’s discovery was seen as “sunlight in a bottle.”

Wilson would later spend much of his life using his money to fund new invention projects. He resided in St. Catharines for over seven years, but later moved to Ottawa. When he passed away in 1915 at the age of 55, over 60 inventions were credited to his name.