Telephone

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

The talking telegraph.

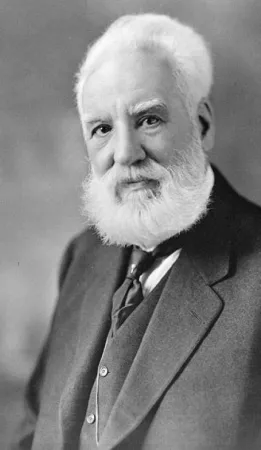

The telegraph seems like such an ancient device. Encoded messages made up of dots and dashes pulsing over a line. Yet in the 1870s, it was the world’s most immediate communications tool, and innovators raced to uncover a way to squeeze more signals down a telegraph wire. Most approached the challenge by trying to get electricity to carry a range of sounds that imitated speech. One man saw the problem differently. Alexander Graham Bell set out to create an electronic appliance modeled on human physiology – the ear, to be exact. He wanted his creation to be an extension of the human being and not merely an enhancement of an imperfect device. This thinking stemmed from two facts: Bell was a speech pathologist and teacher of the deaf who had a keen understanding of the human voice. He cultivated much of that knowledge while living in Brantford, Ontario where he first began to study the human voice experiment with sound in a workshop he called his “dreaming place”. He also benefited from examining the complete structure of the human ear. (Don’t worry, it came from a cadaver.) Only then did he appreciate how delicate its construction and sensitive its ability. After the 1874 innovation was unveiled, Bell himself summed up his advantage succinctly: “Had I known more about electricity and less about sound I would never have invented the telephone.” His talking telegraph remains meaningful, enabling today’s world to reinvent continually how it communicates. Its voice reverberates across the years, as clear and brilliant as ever.