The Comhandi: a Voice for the Voiceless

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

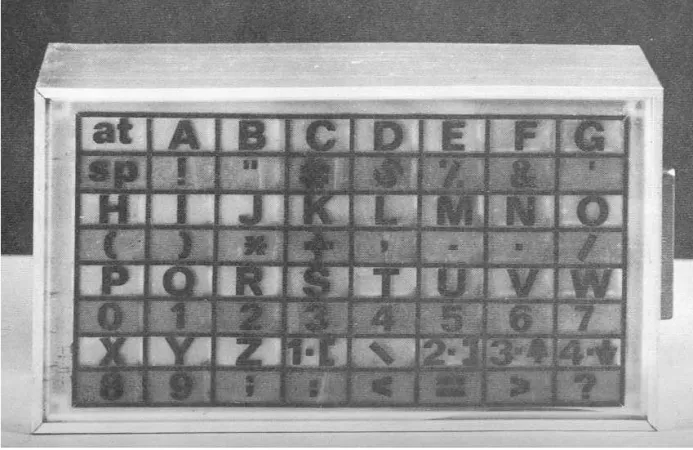

There was a time in Canadian History when people mute by paralysis were neglected, and their capacity for communication barely considered by the rest of society. In the 1960’s this mindset was swept aside with the invention of the Comhandi, an electronic letter-board designed as a tool for children with motor impairments.

The Comhandi would allow kids suffering from disorders like nonverbal cerebral palsy to have their voices heard through their inputs on the keys. This way they could communicate via printouts, symbols and artificial speech. Kind of like a small computer with very specific functions.

In the 60s, there was considerably more attention given to the troubles of people with disabilities because of the crises of the time. The Vietnam War was raging and soldiers south of the border were coming back to the United States with both the emotional and physical scars of war – some maimed to the point of impaired speech.

Thalidomide was a big problem at the time too. The German pharmaceutical drug was designed to offer a sound sleep and reduce morning sickness for pregnant women. It was too late when people discovered that thalidomide could easily cross the placental barrier and cause serious birth defects and even the death of the foetus.

In response to all of this, the National Research Council put together a team to help ease the plight of nonverbal people at the time. The Comhandi was invented in Ottawa by Orest Z. Roy, Raymond Charbonneau and a biochemical engineering team from the NRC.

Charbonneau became a legend and was known as the “Toy Man” at the Ottawa Hospital Treatment Centre, which is a section of the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. The children of the hospital gave him that name because he’d drop by with the devices he and his team created. To the kids, they seemed more like toys than tools for communication. You can see this in the design of the Comhandi, which may be a very simple computer but doesn’t look too different from speech-oriented toys children still enjoy today.

As successful as these devices were, they were very difficult to sell with such a niche market. With the help of member of parliament, Walter Dinsdale, the team created Technical Aids and Systems for the Handicapped, or, TASH. The company was designed to market all kinds of assistive devices. Dinsdale’s son was disabled so he spent much of his life advocating for people with impairments.

The Comhandi was a pivotal tool for communications technology and became the bedrock for so much of the assistive technology we have today. Arguably, it also shifted Canadian society’s treatment of disabled people in the 60’s.

By: Jassi Bedi