Cellular reception: finding a cure for cancer through genetic immunology

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Despite modern medicine and continuous research, diseases like HIV/AIDS and cancer are still taking victims. But significant progress has been made right here in Canada to one day find a method of stopping the diseases from growing in our bodies to begin with. An invaluable contributor to this goal is Tak Wah Mak, a Chinese-Canadian scientist who discovered the T-cell receptor, pioneered the study of genetics in relation to immunology and continues to make great strides in biochemistry to this very day.

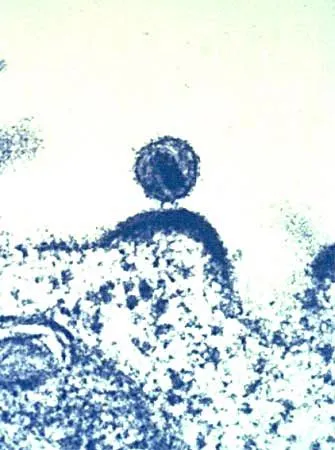

T-cells are cells that look for antigens, which are invaders in the body, like pollen or a cold virus. Each T-cell is unique in that they’re programmed to find one specific antigen. Antigens get stuck to macrophages, which are white blood cells that round up these intruders for T-cells. Mak first identified the receptors on a T-cell in 1980, which look like Y-shaped structures. There are about five thousand receptors on each cell. If the antigen stuck to the macrophage isn’t recognized by the T-cell, it’s safe. But if the T-cell’s receptors match the antigen it calls in its friends.

Chemical signals are sent to call B-Cells, which create antibodies. Antibodies swim around the bloodstream and look to destroy the antigen in question. The T-cell also calls for killer T-cells which also aim to hunt down the invaders. They all divide rapidly and compose an army of four million in just a few days to ward off the sickness.

However, killer T-cells are so effective it can be detrimental to the body. The AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) virus is notably sinister because it’s one of few viruses that attacks T-cells directly. It enters T-cells and forces them to make AIDS proteins on their surfaces. So killer T-cells see the infected T-cell as a threat and kill their own kind. Since there’s only one T-cell that looks over a certain antigen if it dies nothing is left to organize a fight against the invading bodies. With the immune system destroying itself people who suffer from AIDS often die of something that is normally treatable.

Mak’s discovery of how T-cell receptors work in the immune system sheds a lot of light on the mystery of autoimmune disorders. Yet, his contributions to biochemistry don’t end there. He’s also one of the first people in the world to do studies with knock-out mice.

A knock-out mouse is a mouse that’s had one of its genes deleted, specifically one that contains instructions on creating a certain protein. Studying a mouse with one of its genes knocked-out can show what that protein did now that it’s absent. This can range from behaviour, health or physical traits.

Fruit-flies grow faster than mice, so Mak’s done a lot of research with them to figure out how to treat cancers and turn a process called apoptosis on or off. Apoptosis is programmed cell death. If a cell has bits of a virus in it, it would kill itself. Too much apoptosis can cause cell loss disorders and too little can cause uncontrolled growth, like with a cancerous tumour.

Mak now works on targeted therapeutics, which are drugs that only target diseased cells. In 1999 he found out which gene facilitates the growth of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Knocking it out doesn’t affect the body too much so he’s hopeful this may lead to a cure for the disease, instead of the harsh chemotherapy that is currently standard practice.

By: Jassi Bedi

Transcript

00:07

hi my name is Jennifer I heard about the

00:09

immunotherapy what is this about Thank

00:19

You Jennifer for the question

00:21

immunotherapy in short is how to

00:25

galvanize our immune system to fight

00:28

cancer you and I know our immune system

00:32

was built to fight viruses bacteria

00:35

parasites etc and we've been really very

00:38

successful there but the immune system

00:42

can it be used to fight cancer cells as

00:44

well so today we treat cancer patients

00:47

with three different kinds of methods

00:50

one surgery to remove the tumor as many

00:54

as we can find number two radiation we

00:58

use radiations to try to kill the tumor

01:02

and number three if the tumor has spread

01:04

to other places we need to use what is

01:08

called drugs a few years ago scientists

01:12

discovered that if we can take away the

01:15

break of the immune system the immune

01:18

system not only can fight viruses

01:20

bacterias and parasites it can go into

01:23

override to kill the cancer cells and

01:26

this has now been approved in the US and

01:31

in Canada for melanoma a very very bad

01:35

form of skin cancer lung cancer kidney

01:39

cancer bladder cancer and soon to be had

01:44

in that cancer so our understanding is

01:48

almost unbelievable and and and we do

01:51

not even know whether limit of disguise

02:12

you