Breakthrough tech helps doctors more accurately diagnose cancer

This article was originally written and submitted as part of a Canada 150 Project, the Innovation Storybook, to crowdsource stories of Canadian innovation with partners across Canada. The content has since been migrated to Ingenium’s Channel, a digital hub featuring curated content related to science, technology and innovation.

Over-treatment of cancer patients is controversial. Now big data mining of MRI images and CT scans is helping radiologists make the right diagnosis. Corporations use big data mining to find out everything from the kind of car you want to buy to your favorite holiday destination. Now, doctors are using it to make sure when somebody is diagnosed with cancer - they’ve got it right.

Research from the University of Waterloo is taking speculation off the table so radiologists can more accurately determine whether you or your loved one has cancer, and exactly what kind it is, when reading CT scans and MRI images. Getting the diagnosis exactly right with medical images, can mean less invasive testing and unnecessary treatment for patients.

The new technology is showing excellent results, accurately detecting lung cancer 91 per cent of the time. It’s a vast improvement when you consider a recent study showed radiologists looking at CT images were able to detect lung cancer only 55 per cent of the time.

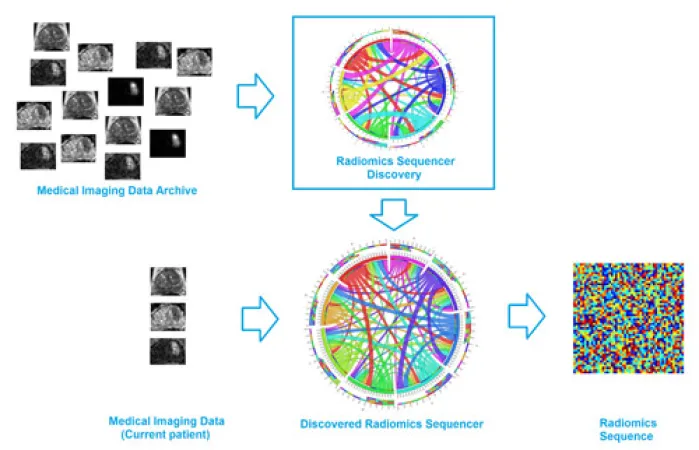

Alexander Wong, a systems design engineering professor and Canada Research Chair in Medical Imaging Systems, is collaborating with doctors Masoom Haider and Farzad Khalvati at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto to develop the breakthrough technology. Called discovery radiomics, it analyzes information from thousands of patients’ images – think terabytes of stored CT and MRI image data – and combines that information to pinpoint hidden biomarkers that indicate specific types of cancer.

Without this kind of personalized data, radiologists pull up images and simply use their years of experience and training to look for signs of disease. Call it extremely educated guesswork.

“But that sometimes ends up boiling down to, ‘here’s a little smudge’ or ‘it’s slightly darker or brighter.’ It’s not very conclusive,” says Wong.

This ambiguity is a real problem in clinical diagnosis using imaging. “At the end of the day, radiologists are people,” Wong explains. “They might make slightly different observations from one day to the next.”

Discovery radiomics, however, helps maintain a level of consistency and accuracy so there are fewer false positives and negatives. And while his original research was based on a similar idea – using existing images to help detect cancer – Wong’s new direction goes much further.

The new technology answers important questions like:

- Exactly what kind of cancer does a patient have?

- How aggressive is it?

- How likely is it that it will require treatment? Or should it be left well enough alone, as is sometimes the case with prostate cancer?

Khalvati, a junior scientist at Sunnybrook Research Institute working with Wong on the project, says the technology’s ability to give more specific information about a person’s cancer could go far in helping eliminate unnecessary treatment and invasive testing.

For instance, prostate cancer often grows so slowly that patients die from other maladies well before the cancer would have caused harm. Or take the example of a lung biopsy, which requires creating an incision and inserting a needle through the patient’s chest cavity. But if radiologists have better imaging data to work with, why bother putting patients under the knife?

“There’s a lot of controversy in terms of over-treatment and over-diagnosis of prostate cancer. A lot of people who go for treatment don’t need to,” Khalvati says. “Our goal is to diagnose accurately and non-invasively so patients will get the treatment they need and save others from unnecessary treatment.”

Eventually, Wong hopes that discovery radiomics will lead to not just detecting cancers, but actually give deeply useful information to help eradicate cancer in the first place. “The more information we have, the better decisions we can make,” says Wong. “That’s going to help patients in the long run.”