Many voices: Oral histories of Canada’s grain elevators

Grain elevators have long been a symbol of agricultural strength for the Canadian prairies. But what was it actually like to work in the grain elevators?

As a practicum student from Carleton University, I have been pondering this question while researching a grain elevator model in the agricultural collection of Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation. Fortunately, I was introduced to Friends of Grain Elevators (FOGE), a non-profit group of volunteers that celebrate grain elevators and their role in Canada’s grain industry. They have interviewed, documented, and shared on their website the experiences of grain trade workers. FOGE included oral histories from people across Canada, and jobs from farm to port, which helped me answer the question of what it was like to work in Canada’s grain industry.

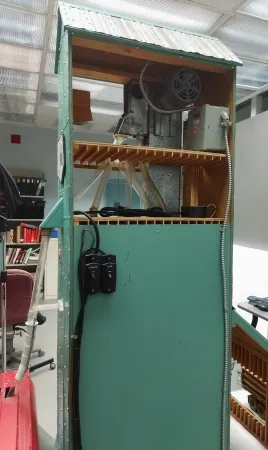

Front view of the grain elevator model.

The growers and nurturers

We must begin with farmers — the lifeblood of the grain industry. Recognizing the importance of the farmers, many of the oral histories captured by FOGE involved questions pertaining to the relationship of the elevators to farmers. Farmers grow and nurture the grain until, at its full maturity, it’s cut and taken to a centralized elevator to be weighed, tested, and stored. Without farmers, there would be no need for elevators.

Farmers were not always as involved in the process. In his oral history, Greg Arason reminisced about his ancestors and how they overcame obstacles such as infertile lands, connecting to the community through farming. Mr. Arason states, “Farmers at the time [early twentieth century] decided that the system as it existed was a disadvantage to them in that they had no say in the business.”[1] Because of this, Mr. Arason’s grandfather helped found Manitoba Pools, with the main goal being more control for farmers. Mr. Arason “think[s] it accomplished a lot of what they had hoped. It did give them a better access to the system. It did give them a share of the earning of their grain after it entered the elevator.”[2] In their hay-day the Manitoba pool elevators, and the two other Pools that were created like it, Alberta Pool and Saskatchewan Pool, handled 50 percent of the grain in the three provinces.[3]

Side view of model, showing how the grain is deposited into waiting trucks.

The caretakers

The oral histories of elevator workers also provide an in-depth look into grain elevators. The role of elevator workers is to take care of the grain after it leaves the farmers; they clean and store it until its transport by railcar or ship. This sounds like an easy process, but it requires lots of sampling, labouring, and mess. FOGE has oral histories from many perspectives of elevator workers, but a recurring theme was the amount of heavy lifting and labouring that the workers had to do. From shovelling and moving the grain, to the manoeuvring of the rail cars, it was considered strenuous and dirty. Dirt was one of the main complaints. Dust from the grain got everywhere, and infestations were always a threat.[4] In the words of Victor Bel, an inspector; “The minute you start moving grain, these places got untidy with grain falling off the belts. The architecture of them was not meant for keeping clean.”[5]

The samplers and inspectors

Samplers and inspectors were an integral part of the grain trade. The dirt and dust of elevators, and Canada’s growing global trade, made these jobs increasingly important. Mr. Bel fondly remembers being nicknamed “Bugman” due to his job of going to the elevators’ ship holds, or storage areas, to check for infestations and extraneous materials.[6] In describing the experience of inspecting ship holds, Mr. Bel stated that “half the time we didn’t know if the ladder was safe or not, because you’d look down and it looked well. But you got there and you put your hand on it and the rail was broken. And of course, we never had any safety apparatus like a rope or anything.”[7] Mr. Bel tells of long hours, working in the dark, and slippery rain or freezing conditions,[8] all of which could lead to potential injury and even death.

However, Mr. Bel was adamant that inspection was one of the most important parts of Canada’s international success.[9] Mr. Bel and the men he worked with were very through inspectors, making sure that regulations set out by the government were kept. The workers became well known for not taking bribes and being fair inspectors. It was because of these strict regulations that Canada earned a global reputation for standards and professionalism.

Close-up view of the Alberta Pool sign and the outside mechanism for depositing grain.

The forgers of new ground

Part of answering the question of what it was like to work in the grain trade is looking at varied experiences. Among its diverse samples of oral histories, FOGE included some of the first women to work in the grain trade. Gale Fickus, who worked as a sampler in the late 70s, reflected on women’s role in the grain industry by saying, “We were breaking tradition. We were coming in to labour and I don’t think they were quite prepared as to how to deal with us and it caused a lot of confusion.”[10] While she still had to do the full job of a sampler, the same broken ladders and slippery boats, she did not enjoy the same familial comradery as male inspectors like Victor Bel. Instead, she was met with animosity and harassment. She says, “The women were such a novelty and we were preyed upon to be something that was nice to have in the office to look at.”

At the time, this harassment for women was considered acceptable. Ms. Fickus states, “I think a lot of us thought that if we are going to break ground in a male world than this is some of the stuff that we are going to have to put up with.”[11] It was because of this harassment that Ms. Fickus left the grain industry. After an incident at one of the elevators where, out of spite, one of her coworkers sent her to sample potential mercury contaminated grain without telling her, she felt she could take no more.[12]

It took time for men, who had dominated the grain industry, to accept women such as Ms. Fickus. That did not stop the women though. “We all felt we were revolutionary. We were quite proud of ourselves,”[13] she says. “We just thought, ‘look at us — we are women and we are doing something different and the opportunity is here; we are coming on and we are going to do it.’”[14]

These oral histories were a great source to answer my question of what it was like to work at a grain elevator. By recording and sharing these oral histories, FOGE shows a more intimate and complete history of the grain trade. The different experiences and voices show that there is not just one history, but many. Paired with an artifact like the grain elevator model, they preserve the legacy of grain elevators and create a connection to Canada’s history.