A colourful, family history shines behind a soil test kit

Behind a single artifact, there are many interwoven stories.

Recently, as a practicum student from Carleton University, I had the chance to research artifacts that belong to the agricultural collection of Ingenium – Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation. Through this work, I uncovered an interesting family history behind a soil text kit from the 1960s.

The museum acquired this soil test kit from the estate of John Allen Martin. Members of his family were kind enough to give a brief history of the Martin family, allowing their story to be preserved with the artifact. The soil test kit lived on the Martin family farm, aptly called The Martin Farm. This farm, and the farm across from it, have a long and connected history.

The Martin Farm was established in 1835 by members of a different Martin family, who were unrelated to the John Allen Martin that would eventually own it. In 1915, the farm and its effects were bought by John Francis Martin. It is not mentioned in the sources how he was related to John Allen Martin, just that they were family. The relationship between the two Martin families is unknown, but they did live close to each other before the Martin farm was bought by John Francis Martin.

The second farm that was involved with the Martin family was located just across the road; this farm was owned by the Batley family. Elsie May Batley, the family’s only child, inherited this farm when her parents passed away. It had been passed down from her grandparents to her parents — along with all objects on the farm — many dating from the 1800s. These families were then brought together through love. After living across from her for many years, John Francis Martin married Elsie May Batley.

John Allen Martin inherited the farm, but the source does not say when. In 1940, John Allen Martin’s brother (whom the source does not name so I will call him Mr. Martin) bought the Batley farm and its effects, officially integrating it into the Martin family. Mr. Martin worked and lived on the Batley farm until 1972, when he decided to sell it. Keeping all the effects and furniture, he moved to his family home, The Martin Farm. He lived and worked the farm with his brother, John Allen Martin, and his sister in law, who is not named.

John Allen Martin and his wife eventually moved to Sherbrook in their later years. Mr. Martin decided to stay and continue to work on the farm until his last days. He passed away in the 1990s. His family donated the farm’s extensive collection after his death. This way, the story of the Martin Family Farm lives on through their possessions.

It is due to the passing down of both farms and their effects through the same families that their stories are able to be told. Both farms were considered mixed farms, which meant that there was no one specific crop that created their income. Instead, the farm was likely to have used a variety of crops and/or animals to provide income. For example, the outbuildings on the farm showed signs of housing horses, cattle, and poultry as well as being used for maple syrup production. There was a significant number of agricultural products that had been kept in good condition. Mr. Cloutier, J. A. Martin’s nephew, said that his uncle wanted to employ the scientific method to his fields, which is why they had a soil testing kit. This kit and his nephew’s recollection, combined with other artifacts, such as a two-part milking stool, showcase the Martin family’s personality and devotion to their farm.

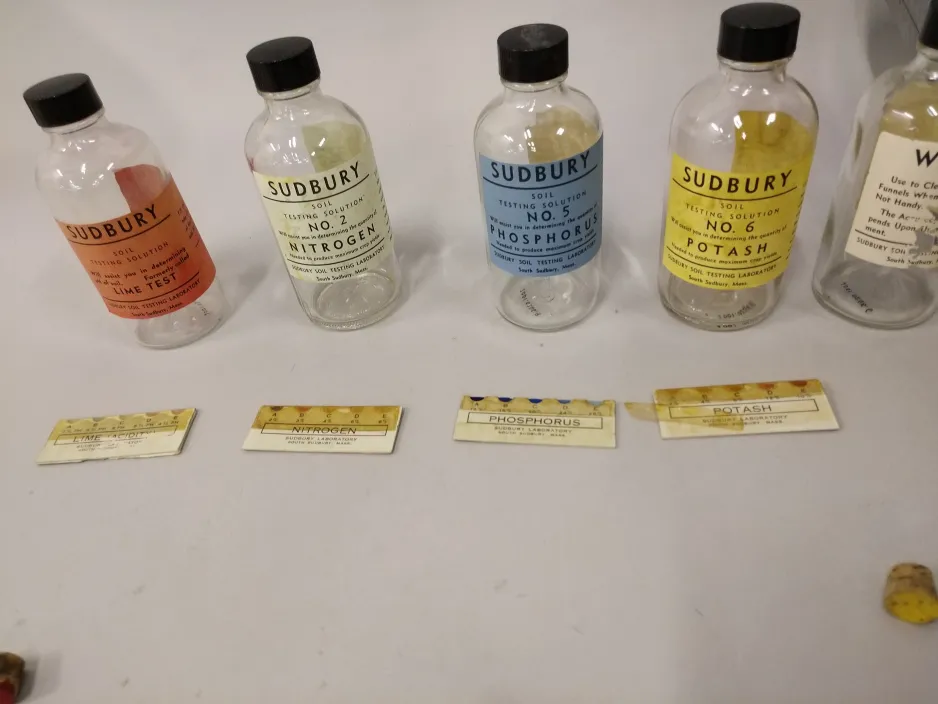

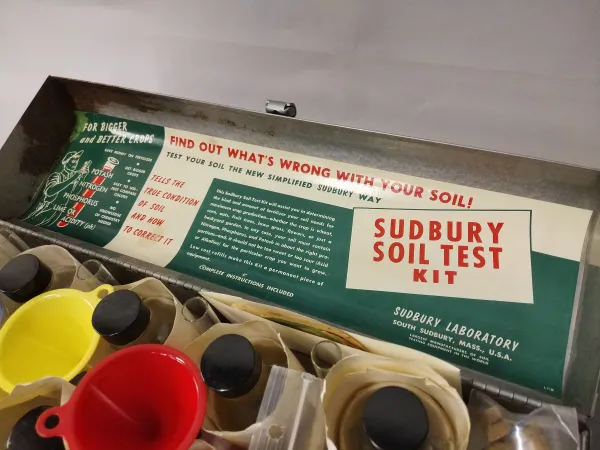

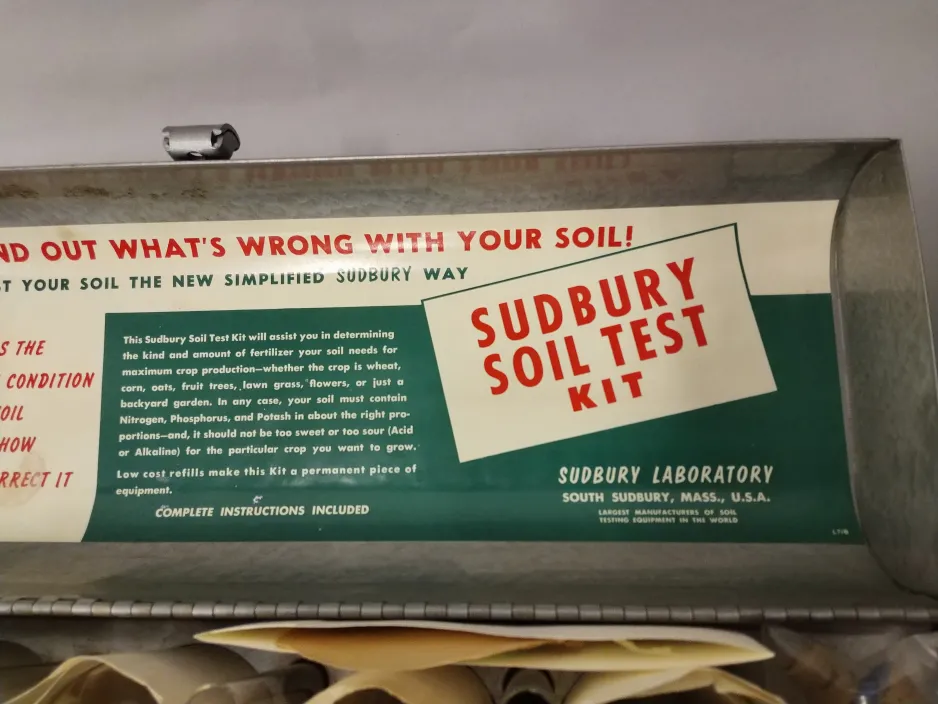

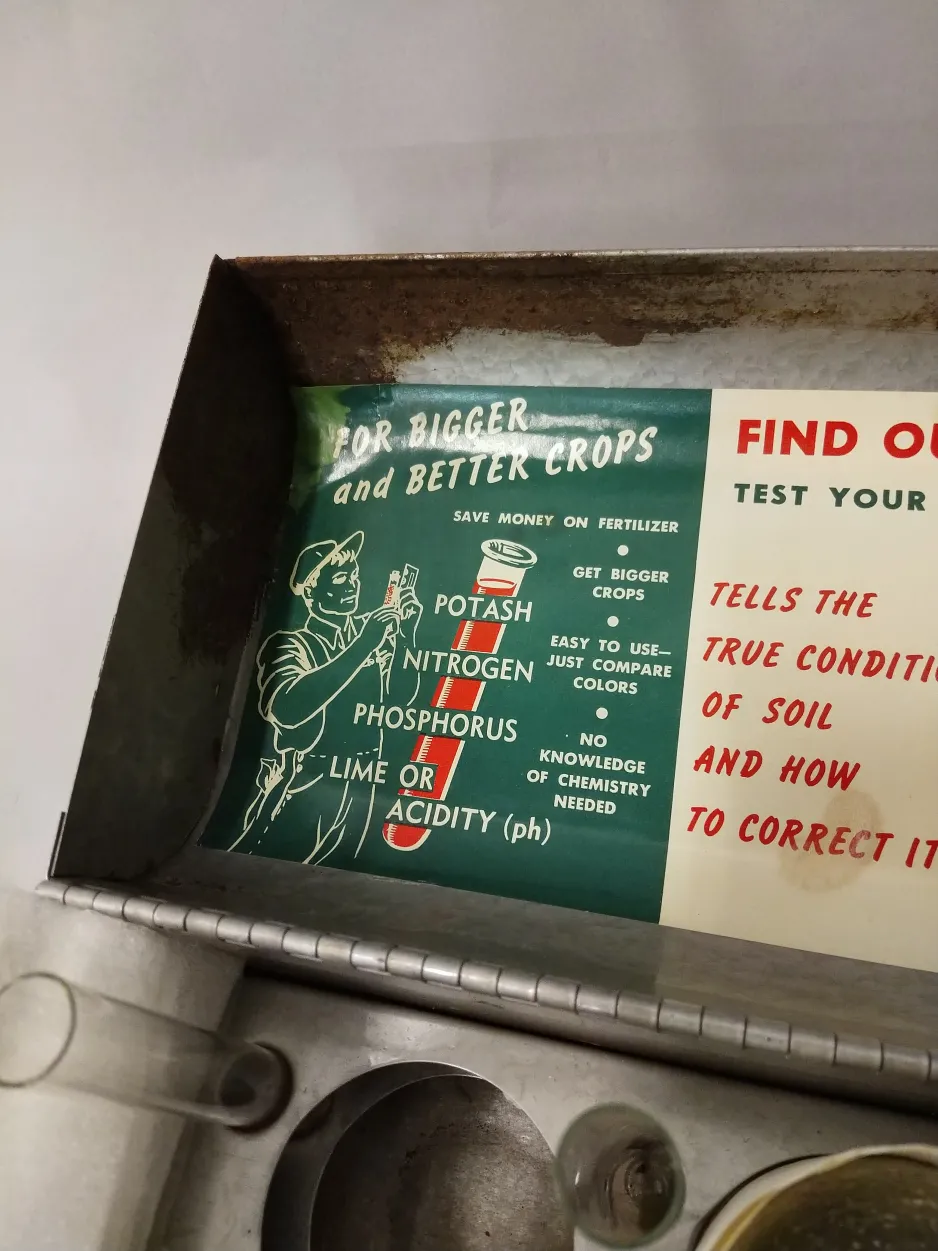

The soil test kit is beautiful isn’t it? It was probably used in the 1960s. It looks bland on the outside, but when it’s opened it explodes with colour, apothecary ingredients, and chemistry experiments. The kit includes bottles of chemicals such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potash, as well as colour-coded funnels and stoppers. Donated with it were test tubes in a homemade rack.

The soil kit came from Sudbury Laboratory in Sudbury, Mass, USA. Looking at the kit and why it was created brings another aspect to the story of these farms. Through the company name on the side of the kit, I was able to track down information on the founders, Herbert and Ester Atkinson. In 1927, they bought the Obadiah Perry farm, dubbed “Home Plate” from Babe Ruth. This was where the company Sudbury Laboratory was created. The Atkinsons started operations in their barn, where they were one of the first to produce a soil testing kit that could be done at the home by anyone.

Farmers’ use of chemical fertilizers was not widespread before the 1960s; their application was generally limited to high-value crops such as tobacco, fruit, and sugar beets. In the 1960s, farmers increasingly turned to fertilizer, which promised noticeable yield increases, with chemicals such as potash and nitrogen to boost the fertility of their soil. For farmers, the soil test kit made it faster and easier to gain knowledge of the mineral content of their soil. Farmers could then easily figure out what fertilizer would increase fertility. For Mr. Martin, this helped him to apply the scientific method to his farming practises, making the soil test kit a vital part of his story.

Soil test kits were popular for a long time, and are coveted by select people today. However, the Sudbury Laboratory it seems has since shut down, the sources do not specify when, where, or how. It is lucky that one soil kit — with such a rich, personal story — has made its way unharmed to the national science and technology collection, where it can shine in its colourful glory.