I spy with my little stabilised and steered camera eye

Hello there, my reading friend. How are you today? Good, good. Personally, I feel reasonably well. I have a feeling that the management of the Electronics Division of Canadian Westinghouse Company Limited of Hamilton, Ontario, felt more than reasonably well 50 years ago, on 3 April 1969 to be more precise, when the British weekly magazine Flight International published the article at the core of this week’s peroration. As was / is / will be often the case in matter of science, technology and innovation, the development of the device that caught my spying eye had begun well before 1969.

Let us turn back the clock, my reading friend, and proceed backward and downward into the dark reaches of time. Did you know that Canadian Westinghouse played a pioneering role in the history of Canadian unpiloted aerial vehicles, and this even before 1960? This company and the Canadian Armament Research and Development Establishment of Valcartier, Québec, an element of the Defense Research Board and today’s Defense Research and Development Canada Valcartier, worked with the British company Servotec Limited to develop the latter’s Periscopter, a captive battlefield surveillance unpiloted aerial vehicle. And yes, my reading friend, the word Periscopter was created from the words PERIScope and heliCOPTER. Launched around 1959, this most interesting project was abandoned around 1966-67.

This being said (typed?), the team of Canadian Westinghouse engineers led by John Noxon “Nox” Leavitt kept working on the stabilised camera system which was to be one of sensors that could be mounted on the Periscopter. The road to success was paved with serious difficulties that Leavitt and his team proved able to overcome.

The end result of their hard work was a military surveillance system known as the WEstinghouse Stabilised and Steered CAmera Mount (WESSCAM). The master component, dare one say the secret ingredient of this device was a steered gyro-stabilised platform housed inside a fibreglass dome. Said platform enabled a television or movie camera mounted on an air, land or sea vehicle moving forward or backward, up or down or sideways to capture images that were as clear and vibration free as those taken by a camera placed on a tripod sunk in a slab of concrete. The camera itself could be pointed in any direction, by remote control, by an operator aboard the vehicle. Mind you, a WESSCAM could also be mounted on a crane. Incidentally, an operator could control a WESSCAM from a distance of about 90 metres (environ 300 feet).

The Canadian Westinghouse WESSCAM, the first successful device of its type to go into production, may have been displayed for the first time at the 28ème Salon international de l’aéronautique et de l’espace, held at Le Bourget airport, in a suburb of Paris, in May and June 1969.

In 1974, Canadian Westinghouse divested its defence division, selling the WESSCAM’s patents and the lab equipment to some managers, including the aforementioned Leavitt. The latter promptly formed Istec Incorporated. Leavitt retired in 1984. Istec became Wescam Incorporated, with one S, in 1994. The company, which had moved to Flamborough, Ontario, at some point, moved to Burlington, Ontario, in 2000. An American firm, L-3 Communications Holdings Incorporated, today’s L-3 Technologies Incorporated, acquired Wescam in September 2002. Leavitt died in April 2009. He was 88 years old.

Over the past 50 years, Canadian Westinghouse / Istec / Wescam developed a bewildering variety of surveillance systems for armed forces and law enforcement agencies around the world. Said systems were / are mounted on air, land and sea vehicles, from large helicopters and aircraft to unpiloted surface vessels – the naval equivalent of an unpiloted aerial vehicle. These systems incorporate several types of sensors, including high definition cameras for daytime and night time operations.

All in all, said systems have been / are used in 70 countries across the globe, on 135 or so types of air, land and sea vehicles, both piloted and unpiloted. The great majority of the systems manufactured by the company are sold to foreign buyers. Wescam is undoubtedly a world leader in its field.

Mind you, some of these systems have also been used by the entertainment industry, and this is where our story becomes complicated. You see, my reading friend, back in 1971, a short time Canadian Westinghouse employee by the name of Ron Goodman modified the inner workings of the WESSCAM while working in Europe and began to market this modified device under the name X Mount. As months turned into years, his reputation as an aerial photography wizard grew. Goodman, who was Canadian, moved to the United States in 1984. He and a partner improved the X Mount, turning into the Gyrosphere. The new device proved very successful. Goodman founded SpaceCam Systems Incorporated in 1989. He and it have won many awards over the years. If truth be told, Istec was sufficiently impressed, or concerned, that it improved its own designs in light of what Goodman had done. SpaceCam Systems still existed as of 2019.

Around 1984-85, an American entrepreneur and pilot by the name of Dan Wolfe signed a joint venture project with Wescam Systems International Incorporated, a technical support and rental branch of Istec. One of his companies, Pasadena Camera Rental Incorporated, began to offer Wescams to American movie makers. As time went by, Wolfe realised that the Canadian device was not quite tough enough, and neither was the Gyrosphere. He founded Gyron Development Group and Gyron Systems International Limited well before the end of the 1980s to come up with a better stabilised camera system. The new device was introduced some time later. Gyron Systems International still existed as of 2019.

If truth be told, Wolfe was not the only individual inspired by the Wescam and the Gyrosphere. Several companies in the United States launched comparable systems, with more or less success.

In 2004, Wescam spun out its entertainment division, including the rights to a motion management technology known as XR, which led to the creation of PV Labs Limited of Hamilton, Ontario. The company was still going strong as of 2019. It even had an American subsidiary, Pictorvision Incorporated. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded a plaque to both companies in 2012 for the development of the Pictorvision Eclipse, a high performance electronically stabilised aerial camera platform launched in 2008.

Given this bewildering technological ballet, yours truly cannot say if the scenes shot in a particular film were made with a WESSCAM / Wescam, an X Mount / Gyrosphere, a Gyron, an Eclipse, or something else altogether. WESSCAMs were apparently used by the motion picture industry before the end of the 1960s, however, in movies like Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, of 1969, and Tora! Tora! Tora!, of 1970, a spectacular if financially disappointing blockbuster about the Japanese attack against the Hawaiian Islands in December 1941. The elaborate maze shots of the 1972 American British mystery thriller Sleuth would have been all but inconceivable without the use of a WESSCAM. Did you know that the famous scene showing Leonardo Wilhelm DiCaprio and Kate Elizabeth Winslet at the bow of the RMS Titanic, in the eponymous 1997 blockbuster movie, directed by the Canadian James Francis Cameron, was seemingly filmed with a Wescam?

A short digression if I may. One of the most famous aeronautical songs of the Belle Époque, Come Josephine In My Flying Machine, composed in 1910, came out of oblivion when DiCaprio and Winslet interpreted it during this film. It should be noted that the songwriter of this work, Alfred Bryan, was a Canadian.

And yes, my reading friend, one could argue that yours truly made a booboo when I wrote the title of a February 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee. Said title could, yes could, have read Come Jasmine In My Flying Machine. I chose otherwise. Sue me, but back to our story.

The magnificent 2001 French documentary / docudrama Winged Migration included footage filmed during storms that could not have been made without the use of a stabilised camera, seemingly a Wescam. I would not bet an hour’s salary on that statement, however.

It is worth noting that Winged Migration may have been inspired in part by William Ayton Lishman, a successful Canadian sculptor well known for his pioneering efforts in imprinting migratory birds so that he could fly with them in an ultralight aircraft. The world famous, dare I day amazing and mind blowing, collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, Ontario, includes 2 ultralight aircraft donated by Lishman, namely an Ultralight Flying Machines Easy Riser used to test his bird migration ideas and a Cosmos / Cosmos ULM Echo owned by William Lishman & Associates Limited used to put in practice said bird migration ideas.

Would you believe that many images of the Games of the XXI Olympiad, held in Montréal, Québec, in 1976, were filmed by one or more WESSCAMs? One only needs to think about the filming of the journey of the Olympic flame or the closing ceremonies. For the rowing competitions, a WESSCAM was mounted on the vehicle used by the trainers. For the cycling competitions, a WESSCAM was mounted underneath the clock of the Vélodrome and at an intersection in Montréal. In 1996, a Wescam was on hand when Canadian sprinter Donovan Bailey won the gold medal for the 100 metre race at the Games of the XXVI Olympiad, held in Atlanta, Georgia. Operated by remote control, it was mounted on a track mounted next to the running surface.

All in all, Canadian Westinghouse, Istec and Wescam may have won no less than 17 Emmys and 2 Oscars. I hear (read?) that 2 of the Emmy awards came in 1989 and 1991 as a result of the work done by Istec for television special presentations, The Magic of David Copperfield XII: The Niagara Falls Challenge of 1990 and Paul Simon’s Concert in the Park of 1991. This being said (typed?), most of the Emmy awards given to Istec and Wescam came as a result of sport programs broadcasted by ESPN Incorporated.

Indeed, many images of races organised by the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing or championship games of the National Football League known as Superbowls seen on television since the early 1990s were captured by Wescams or some other type if stabilised camera, possibly carried on a helicopter, drone or blimp. Did you know that a Wescam was apparently used as early as 1983, during the Fiesta Bowl game – a world first for such an application? At the 2001 X Games, an extreme sport championship sponsored by ESPN, a cyclist taking part in a downhill BMX competition ran the course with a Wescam system built into his helmet.

While one of the Oscars was awarded for the work done in the 1988 American romantic comedy / drama Working Girl, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognised Istec in 1990 for the invention of the WESSCAM / Wescam and the continuing development of this technology. Goodman was similarly recognised in 1996 for his work on the X Mount and Gyrosphere.

The continuous, 8 minute shot near the end of the 1975 Italian French Spanish drama Professione: reporter, in English The Passenger, seemingly the longest uncut shot ever filmed, was shot using an X Mount, and not a WESSCAM. The same could be said in the case of aerial sequences in Superman and The Empire Strikes Back, 2 very successful movies premiered in 1978 and 1980.

Would you believe that the aforementioned Eclipse was used during the filming of 5 of the top grossing live action motion pictures premiered in 2011, namely The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Part 1, Fast Five, The Hangover Part II, Rise of the Planet of the Apes, and Thor. And yes my cinematically savvy reading friend, Eclipses were also used during the filming of at least 2 of the top grossing live action motion pictures premiered in 2012, The Dark Knight Rises and The Amazing Spider Man. Eclipses were still used with a great deal of success as of 2019.

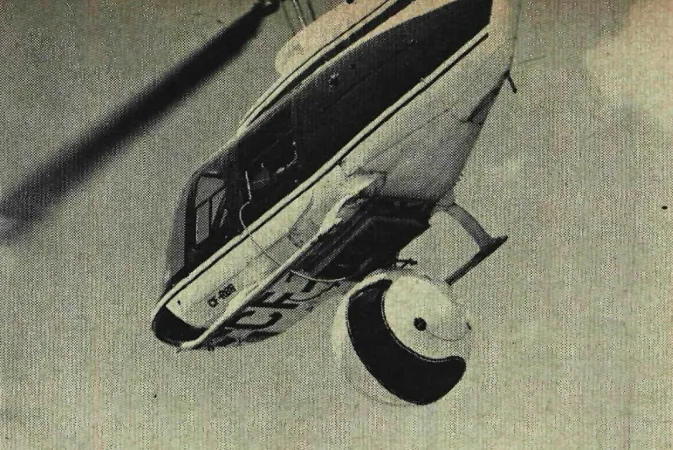

A Bell LongRanger of the Canadian Coast Guard delivering an individual to rescue workers, Marblehead, Ohio, December 1998. Wikipedia.

May I be permitted to digress for a moment? You may have noted, or not, that the caption of the photo at the beginning of this article mentioned that the WESSCAM, with 2 Ss, was mounted on a Bell Model 206 JetRanger. It so happens I have information on this helicopter. Resistance is futile.

The helicopter in question was the 10th Model 206 produced by Bell Helicopter Company, a subsidiary of Bell Aerospace Corporation, itself a subsidiary of industrial giant Textron Incorporated, and one of the first, if not the first helicopters of this type registered in Canada. Its first owner was a radio station in Toronto, Ontario, known as CFRB, which was owned by Standard Broadcasting Corporation, a subsidiary of Argus Corporation. One of the oldest surviving stations in Canada, CFRB was founded in early 1927 by Rogers Vacuum Tube Company, an ancestor of today’s Rogers Communications Incorporated, a giant in Canadian communications. It was founded, say I, to promote a batteryless radio receiver invented by company founder Edward Samuel Rogers. And yes, my reading friend, the letters RB in CFRB stood for Rogers Batteryless. Would you believe that Rogers Communications was mentioned in a January 2018 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee?

Visible from 100 kilometres (more than 60 miles) away, CFRB’s gigantic, 165 to 170 metre (550 feet) transmitting antennas count among the landmarks of Toronto. Pilots coming to land at 1 of the 2 nearby airports regularly use them as landmarks.

Did you know that the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s iconic radio show Hockey Night in Canada owed / owes its origin to General Motors Hockey Broadcast, a program aired for the first time in 1932, by CFRB? And yes, my reading friend, the CBC was mentioned on many occasions in our blog / bulletin / thingee, and this since September 2018.

Our story begins in 1960 when the United States Army launched a competition for a light observation helicopter capable of performing the various duties of the aging helicopters and airplanes in its inventory, One of these aging machines, the Bell H-13 Sioux, can be found in the collection of the Canada Aviation and Space Museum, in Ottawa, in the form of an HTL operated by the Royal Canadian Navy. Both the Sioux and the HTL were / are versions of the world famous Model 47 helicopter.

Given the potential size of the United States Army’s orders (up to 4 000 helicopters over a decade according to some sources – a figure never seen before), interest in the American aerospace industry was high and no less than 12 makers submitted proposals. Three of these were chosen for final evaluation in 1961, among them the Bell Model 206. As was the case with its competitors, 5 prototypes of this helicopter were constructed. The first HO-4 / OH-4 flew in December 1962. Unfortunately, the Ugly Duckling, as it was called, was deemed inferior and eliminated from the competition. In May 1965, the United States Army announced that a newcomer in helicopter manufacturing, the Aircraft Division of Hughes Tool Company, had won. The performance of its elegant and compact OH-6 Cayuse was deemed superior and its price seemed very attractive indeed. And yes, that company was owned by Howard Robard Hughes, Junior. Hughes and / or his company were mentioned since October 2917 in various issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Did you know that the helicopter seen in the television series Magnum, P.I., broadcasted between December 1980 and May 1988, was a civilian version of the Cayuse? Better yet, the Hughes 500 / MD 500 was still in production in the United States in early 2019 in the factory operated by MD Helicopters Incorporated, a subsidiary of Patriarch Partners Limited Liability Company.

At time the victory of the Cayuse was announced, the marketing team at Bell Helicopter was developing a civilian derivative of the OH-4. Indeed, design work began in April 1965. Very early on, it was thought best to design an entirely new and rather more spacious fuselage. Sadly, the company had no money to spare for such a redesign. The marketing team had to be creative. If truth be told, it did not seek management’s permission to proceed. The marketing team contacted 2 design companies that were under contract to Bell Helicopter and asked them to work on proposals whose costs would be hidden within various contracts.

Unsatisfied with the results, some team members came up with a proposal of their own. Company executives were suitably impressed by a full-scale mock up of this new streamlined 5-seat fuselage which kept intact the costly mechanical components of the OH-4. Development of the new helicopter, still known as the Model 206, was approved. And yes, my reading friend, that Model 206 was mentioned in an October 2017 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

Construction of a prototype began in July 1965. This machine flew in January 1966 – according to most sources. That same month, the prototype was presented at the convention of the Helicopter Association of America, in Texas. In April, Bell Helicopter sent the prototype on a 3 and a half month promotional tour during which it visited many sections of the United States (16 states and the District of Columbia) and Canada (4 provinces). The Model 206 received its type approval certificate in October. By then, a powerful member of the management team, a company president perhaps, had picked a name for it. Production of a version of the very successful Model 47 helicopter known as the Ranger was ending and he thought that JetRanger sounded just about perfect.

Deliveries began in January 1967. Before long, many people in the industry were saying that the JetRanger was one of the most elegant helicopters ever built – a textbook case of an ugly duckling turning into a beautiful swan. To keep up with orders, Bell Helicopter outsourced production of fuselages for both civilian and military Model 206s to Beech Aircraft Corporation. In addition, by the time 1967 ended, a second production line was ready, in Italy at the facility of Costruzioni Aeronautiche Giovanni Agusta Società per Azioni, a company mentioned in the February 2019 issue of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

If things seemed on the up and up for Bell Helicopter, the same could not be said for Hughes Tool. Delays in deliveries and production costs of the Cayuse had increased to such an extent that the United States Army reopened its light observation helicopter competition in 1967. An announcement made in March of the following year thrilled everyone at Bell Helicopter. The United States Army ordered 2 200 OH-58 Kiowa – the largest single order so far for a helicopter anywhere in the world. Deliveries began in May 1969.

This being said (typed?), the Kiowa was not the first version of the Model 206 to be ordered by the American military. In 1967, the United States Navy identified the need to find a new primary training helicopter to replace the aging machines in its inventory. The acquisition of a civilian type right off the shelf seemed like a good idea. In January 1968, the USN ordered 40 TH-57 SeaRangers. Deliveries were completed before the end of the year.

As time went by, Bell Helicopter or, as it was called from 1976 onward, Bell Helicopter Textron Incorporated, a division of Textron, introduced improved civilian versions of the Model 206. The very first of these was ordered by Okanagan Helicopters Limited, a well known helicopter operator from Canada. In Australia, Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation built about 45 JetRangers for use by the Australian Army between 1973 and 1977. Although officially christened Kalkadoon, they were universally known as Kiowas. Costruzioni Aeronautiche Giovanni Agusta continued to produce JetRangers for military and civilian operators in Italy and elsewhere. The last Italian-made AB206, as these machines were known, left the factory around 1991. And yes, Okanagan Helicopters was mentioned in October 2017 and October 2018 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee.

It is worth noting that, in August 1982, Richard Harold “Dick” Smith left the Bell Helicopter Textron factory at the controls of a JetRanger. The goal of this Australian businessman fascinated by the long distance pilots of the 1920s and 1930s was nothing less than the first solo round the world flight in a helicopter. That same month, Smith landed in the United Kingdom, thus becoming the first person to cross the Atlantic alone in a helicopter. He made it back to Texas in July 1983, after covering a distance of about 56 750 kilometres (slightly more than 35 250 miles) without experiencing any significant mechanical problem.

Eager to put on the market a helicopter able to fill the gap between the JetRanger and its larger designs, Bell Helicopter designed a stretched version of the Model 206 in 1973. Deliveries of the 7-seat LongRanger began in 1975. Improved versions soon followed. The LongRanger proved very popular with emergency medical services because of its large cabin.

A few LongRangers made headlines in the early 1980s. In September 1980, 2 West German pilots, Werner Röschlau and Karl Wagner, completed the first transatlantic flight in a light helicopter. In September 1982, 2 Americans, Henry Ross Perot, Junior and Jay Coburn began and completed the first round the world flight in a helicopter. Their helicopter was donated to the National Air and Space Museum of Washington, District of Columbia.

Do you have time for a digression, my reading friend? All right, all right, do you have time for a digression within a digression? No? No matter. This is too cool a story to ignore. The lack of helicopter production in Canada before the 1980s was surprising to many observers. In a speech made in October 1973, for example, the Minister of Supply and Services, Jean-Pierre Goyer, stated that it was incomprehensible that Canada, in the forefront of the use of helicopters in the world, had an aircraft industry that had virtually ignored this wide potential market since the Second World War.

The birth of a Canadian helicopter industry with design, development and production capabilities dates back to the first half of the 1980s. An interdepartmental working group of the Department of Industry, Trade and Commerce defined the capabilities of the aerospace industry in that field during the summer of 1982. It also examined the global helicopter market to assess the chances of success of a Canadian-based helicopter industry. The stakes were high. Indeed, the department estimated that the purchases of helicopters and parts by Canadian operators alone could reach 3 billion dollars between 1982 and 1992. Let’s not forget that the Canadian market for civilian helicopters was / is the second largest in the world, after the American market. None of these machines were manufactured or even assembled in Canada.

One of the options discussed by the working group concerned a joint venture involving a foreign helicopter manufacturer. Such an approach would facilitate the development of new helicopters, a risky and so expensive process that only a few major companies had the necessary financial resources. Many observers noted, however, that the Canadian helicopter market was so diverse that no locally produced machine could be delivered in large numbers. Some operators also feared that the federal government would charge import duties for the importation of aircraft similar to the one assembled or produced in Canada.

The federal government contacted 8 European and American helicopter manufacturers in December 1982 to indicate that it wanted to improve the capabilities of the Canadian aerospace industry concerning the design, development and production of helicopters. It paid particular attention to light twin-engine helicopters and large helicopters able of meeting the needs of local and foreign operators. The Minister of Industry, Trade and Commerce and Minister of Regional Economic Expansion, Edward C. “Ed” Lumley, stressed that the federal government was ready to invest in such a production project in Canada if potential sales were worth the effort.

Helicopter manufacturers submitted proposals during the first months of 1983. An interdepartmental team evaluated them thoroughly. A well-known French helicopter manufacturer, Aerospatiale Société nationale industrielle, reported that it had begun discussions with Canadair Limited and de Havilland Aircraft of Canada Limited no later than 1982. A British company mentioned in August 2017, May 2018 and February 2019 issues of our blog / bulletin / thingee, Westland Public Limited Company, joined forces with an Italian helicopter manufacturer, the recently renamed Agusta Società per Azioni, to offer a joint project. The largest West German aerospace company, Messerschmitt-Bolköw-Blohm Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung, and Fleet Industries Limited, an Ontario subcontractor controlled by Ronyx Corporation Limited, did the same.

Bell Helicopter Textron offered to produce on Canadian soil the Model 400 TwinRanger, a 7-seat civil helicopter whose development was launched in February 1983. Hughes Helicopters Incorporated, a subsidiary of Hughes Corporation, considered producing a helicopter at a factory built on the site of Canadian Forces Base Chatham, New Brunswick. The American helicopter manufacturer withdrew from the competition in July, however. The Sikorsky Aircraft Division of United Technologies Corporation, on the other hand, intended to cooperate with Pratt & Whitney Canada Incorporated, a subsidiary of a sister company, Pratt & Whitney Aircraft Division. This writer was not / is not able to confirm whether or not Boeing Vertol Company, a subsidiary of Boeing Company, submitted a proposal.

In October 1983, ignoring the somewhat depressed market in the helicopter sector, particularly in Canada, the federal and Québec governments teamed up with Bell Helicopter Textron to build a plant in the industrial park of Montréal-Mirabel International Airport. Bell Helicopter Textron Canada Limited would produce the TwinRanger as well as a derivative, also civilian, the Model 440. Bell Helicopter Textron planned to manufacture vital components (rotor heads, blades, etc.) for an indefinite period. Ironically, even though the lack of helicopter production in Canada was a major reason for setting up an industry, the fact was that the new company planned to export 80% or more of its production. The construction of the Bell Helicopter Textron Canada plant began in 1984.

Around March 1985, Textron announced its intention to sell Bell Helicopter Textron. This news caused quite a stir in Canada. Some people worried about the future of the Mirabel plant. The American giant abandoned its sale plan in July, when the United States Army launched an inquiry concerning accounting irregularities. Textron apparently repaid a substantial sum before having to face a lawsuit. Bell Helicopter Textron was also experiencing difficult times. In fact, the world market for civilian helicopters had stalled following the collapse of oil prices.

In early 1986, Bell Helicopter Textron learned that the American government did not intend to subsidise the construction of a new plant destined, apparently, to produce the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey, a military vertical take-off and landing aircraft of advanced design then under development. The aircraft manufacturer therefore had to find a way to continue this project without harming the production of its helicopters. It decided to move the assembly lines of its civilian machines away from those that worked for the American armed forces. Bell Helicopter Textron considered installing production of civilian helicopters somewhere in the United States. It soon changed its mind. Modern and underutilised, the Mirabel plant offered the company a door to salvation. The helicopter manufacturer was also aware that many observers in Québec and Canada criticized the limited number of employees at Mirabel and were still waiting for the first flight of a helicopter manufactured or even assembled in the Québec factory.

During the summer, Bell Helicopter Textron proposed to the governments of Canada and Québec that the helicopter production program of its subsidiary be modified. The latter accepted in August. They had in fact little choice. The helicopter manufacturer also transferred the production of the JetRanger / LongRanger to Canada. This restructuring allowed Bell Helicopter Textron to focus its efforts on the development of the Osprey and the production of helicopters for the American armed forces. The first JetRanger and LongRanger assembled in Canada flew in October 1986 and April 1987. Deliveries built up as time went by.

It should be noted that the versions of the TwinRanger powered by American and Canadian engines were discontinued in 1986 and 1987. Bell Helicopter Textron abandoned the Model 440 in early 1987, even before the first flight of a prototype. In either case, the insufficient number of sales largely explained these decisions.

Few American helicopters have been produced in greater numbers or for as long a period as the Bell Model 206 and its derivatives. As of early 2008, about 10 000 had been made in the United States (about 3 950?), Italy (about 900), Australia (about 45) and Canada (about 5 100?), for example. They flew / fly in 60 countries around the globe, primarily with civilian operators (more than 70 % of all Model 206s built). Close to 600 Model 206s could be found in the Canadian civil aircraft register in early 2019. Another dozen or so CH-139s training machines fly with the Royal Canadian Air Force. Production of the Model 206 continued until at least until September 2017, at the Bell Helicopter Textron Canada factory. All in all, the Model 206 is one of the most successful light helicopters of the 20th century.

A final twist to the story of the Model 206 is well worth including at this point. During the first edition of an air show held in Iran held in October and November 2002, a helicopter extremely similar in appearance to it was put on display for the first time. The first prototype had flown some time before. The first production Shahed 278, by most accounts a locally-redesigned illegal version of the Model 206, was exhibited at the 2005 edition of that same air show. Although available for civilian use, the Shahed 278 was / is primarily a military helicopter. The Shahed aviation industries research centre, a subsidiary of Iran’s aerospace industries organisation, itself a dependent of the ministry of defence for armed forces logistics, supervised the production of at least 15 Shahed 278 in the 2000s and 2010s.

It is worth noting that the collection of the aforementioned Canada Aviation and Space Museum includes a Bell CH-136 Kiowa, an OH-58 Kiowa under another name operated by the Canadian military.

This concludes our broadcast for this week. I shall see you soon, in the future.