Uncovering the secrets of the world’s first synthesizer (Part I)

Seventy-five years ago, Canadian physicist Hugh Le Caine began work on a strange, new musical instrument with an equally strange name: the Electronic Sackbut. While you may not have heard of the Electronic Sackbut before, you’ve almost certainly heard of the ubiquitous musical instrument it pioneered: the synthesizer.

This is part one of an ongoing Channel series that will follow Ingenium’s reconstruction of the 1948 Electronic Sackbut, better known as the world’s first synthesizer. Today we’ll look back at the invention of the instrument, as well as the complex secrets that curatorial and conservation experts are working to uncover.

Inventing the Electronic Sackbut

Canadian physicist and composer Hugh Le Caine has been referred to as a “hero of electronic music.” Between 1945 and 1974, he designed over 20 unique electronic instruments. He also advised on the construction of some of Canada’s — and the world’s — first electronic music studios, and composed several early classic electronic music pieces, including Dripsody and The Sackbut Blues.

Le Caine built his first fully electronic instrument, the Electronic Sackbut, in his home studio in Ottawa between 1945 and 1948. He named it the “Sackbut” after a 15th century precursor to the modern trombone. Just as players of the Renaissance sackbut could glide between notes by moving the instrument’s brass slide, so too could players of the Electronic Sackbut achieve a similar effect using the instrument’s modified piano-like keyboard. There was a certain irony and humility in Hugh Le Caine’s decision to give his instrument such a strange name. Le Caine joked that borrowing the name of “a thoroughly obsolete instrument … was thought to afford the designer a certain degree of immunity from criticism.”

He had no way of knowing that his experimental instrument would soon inspire a generation of innovators and lay the technical foundations for the future of electronic music.

The 1948 Electronic Sackbut as it appears today, in Ingenium's permanent collection in Ottawa. (Artifact no. 1975.0336)

A complex design

Central to the Electronic Sackbut’s innovative design was its use of voltage control, a technique that permitted the musician to precisely generate, shape, filter, and blend electronic waveforms to create unique musical sounds. By the late 1970s, when the mainstream market for electronic instruments exploded, this approach would be considered standard practice. But in the 1940s, the idea of applying voltage control to the design of musical instruments was both unconventional and difficult to achieve with existing technology. Indeed, some of the materials and techniques Le Caine employed to realize his novel design are some of the reasons why the Electronic Sackbut remains something of an enigma today. While we certainly know what it did, we are still in the process of learning exactly how.

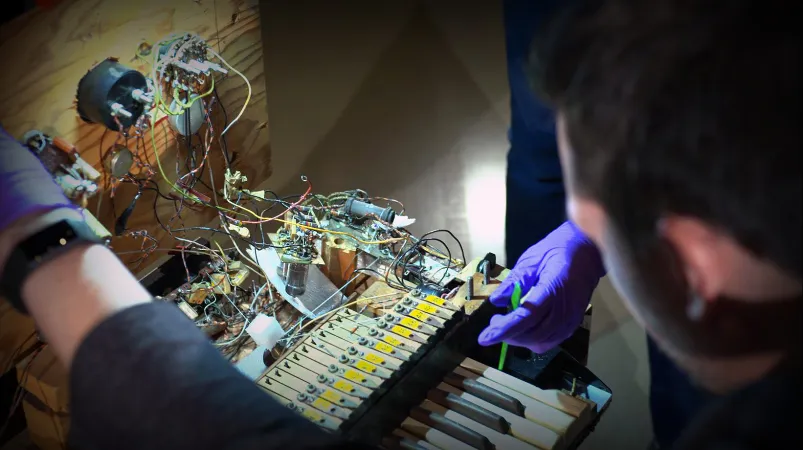

From an electronics point of view, the Electronic Sackbut is an extraordinarily difficult instrument to research. Built as an experimental prototype, Le Caine spent no time making his circuitry look organized, or even removing earlier components that were no longer of use: he would simply snip a wire or break a solder, then move on. The result is what I have affectionally nicknamed “the rat’s nest”: a complex mess of wiring and other components inside the instrument that spills out of its side, back, and bottom casing. Some of this circuity remains essential to the instrument’s operation, and some does not. The challenge is figuring out exactly which is which without untangling the entire system, which would require destroying the remaining connections — and by extension, important historical evidence — in the process.

View under the hood of the Electronic Sackbut, exposing the "rat's nest" of wires, vacuum tubes, and other electronic components.

Aging and unstable components

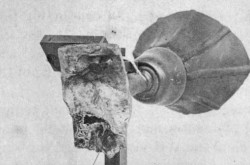

Adding to this complexity is the fact that, today, most of its electronic components are in an advanced state of decay. Manufactured and assembled in the 1940s, most of the electronic circuity has since become brittle and unstable. Just one weak connection point or gap in wire sheathing could pose a serious health and safety risk to potential users and to the artifact itself.

In fact, the only time the instrument has been powered up since Le Caine played it for the last time in 1954 was in 2017, as part of an unprecedented conservation assessment carried out by our colleagues at Studio Bell (National Music Centre, Calgary, Canada).

For two years, renowned synthesizer expert John Leimseider and his team carefully disassembled those components that could be removed non-destructively, in order to determine exactly how the instrument’s circuitry was arranged, as well as which components might still be operational after so many years of aging and disuse. Incredibly, with minimal intervention, he was able to get some of the components — such as its main oscillator, power supply, and keyboard — working again. He was even able to play a few notes on the instrument, allowing us to hear the Electronic Sackbut make sound for the first time in over 60 years, albeit in a stripped down and rudimentary way. John was also able to draw circuit diagrams for several modules, offering us an unprecedented understanding of how the instrument was electronically designed.

Unfortunately, John also confirmed some of our other, considerably lower expectations regarding the condition of many other important electronic components in the instrument: some were impossible to evaluate without forcefully removing (and destroying) other elements, which we weren’t willing to do; others were already too decayed to be functionally restored. In short: without completely removing and replacing most of the instrument’s internal components — a highly destructive form of intervention we were not willing to action on such an important historic artifact — it became clear the Electronic Sackbut would never be playable again.

A closer look at one of the many aging electronic modules inside the Electronic Sackbut. Notice the frayed and exposed wiring, rusted metal solders, and precariously arranged 1940s-era resistors.

After the completion of the conservation assessment in 2017, the instrument was returned to Ottawa and promptly installed in the Canada Science and Technology Museum’s new Sound by Design exhibition. Here it has sat silently, unplayed and unplayable, ever since. As curator of this exhibition, I spent many hours working with designers to display the Electronic Sackbut in a visually approachable way, but lamented the fact that its unpolished physical design betrayed its extraordinary electronic and musical innovations. The best our design team could do was draw on knowledge gained from the 2017 assessment to create a pared-down interactive version of the instrument, installed next to the artifact display. This gave museum visitors the opportunity to experiment with some of the Electronic Sackbut’s core functions and sounds. Yet even this represented a mere fraction of the original instrument’s full musical capabilities; there remained much more to explore.

Uncovering the last secrets

In 2019, following discussions with several museum colleagues, I began to assemble a team to look into alternative approaches to uncovering the Electronic Sackbut’s remaining secrets. In December of that year, our team removed the artifact from its display case and carefully examined its electronic and mechanical components. Our goal was to assess whether it might be possible to disconnect the existing electronic components, and patch in our own custom-built analogue modules — assembled entirely externally to the instrument — so that we might be able to play and hear the original artifact without disturbing its existing internal circuity. This would allow us to safely experiment with different electronic configurations until we arrived at a design that made sense, both technically (in line with knowledge gained during the 2017 conservation assessment) and musically (capable of producing the sounds Le Caine and his colleagues produced when making the few known historical recordings of the Electronic Sackbut between 1946 and 1954). While it still remains to be seen whether patching our own custom-built modules into the original artifact will be technically feasible, we now believe it’s possible to create a reasonably faithful standalone version of the instrument: the world’s first fully playable reconstruction of the world’s first synthesizer.

Jessica Lafrance-Hwang, conservator, examines a conductive metal plate that forms part of the Electronic Sackbut's timbre control module.

In January 2020, the Electronic Sackbut Reconstruction Project officially began. Over the last year and a half, our team has been busy compiling archival documents, sourcing electronics equipment, and assembling a team of experts to consult on the instrument’s design. Our goal is to have our first working prototype finished by early 2022, and our final version completed by end of 2023. This timeline is historically significant. In honour and recognition of Hugh Le Caine’s achievements, we decided to commence the project in 2020, 75 years after he began work on the Electronic Sackbut in 1945, and conclude the project in 2023: 75 years after the instrument was completed in 1948.

Tom Everrett, curator, tests the mechanical action of the Electronic Sackbut's unique vertically- and horizontally-sensitive keys.

In this ongoing Channel series, I will share photographs, videos, and other materials that will provide unprecedented access to this one-of-a-kind artifact, and behind-the-scenes footage of one of the most challenging reconstruction projects our museum has yet attempted. I will also be posting other news and updates on my Twitter feed. On behalf of our entire project team: thank you for reading and for following us on this journey. We’re excited to have you along for the ride.

The Electronic Sackbut Reconstruction Team

Project Lead/Curator: Tom Everrett

Electronics Technician: Jonathan Cousineau

Conservator: Jessica Lafrance-Hwang

Historical Advisor: Gayle Young