Music meets technology: Building a laser harp

If a harp had no strings, could it make a sound?

I put this riddle to the test, when I was approached to make an instrument for the Symphony Hack Lab at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa. The event is designed to “hack the symphony” with new explorations of sound and symphonic classics, created through science and technology.

My challenge was to create a laser harp: an instrument that would use red lasers to project “strings” of light that could then be played like a harp. I have since made two versions, but first let's talk about the original.

The first version I made was a Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) harp. This MIDI harp doesn’t actually make a sound. Instead, it produces musical data when it’s played. In turn, this data is used by a synthesizer (in our case, a laptop with a USB to the MIDI interface) to produce a sound. The sound produced is customizable, and is set by the user; it can sound like a harp, piano, drums, etc.

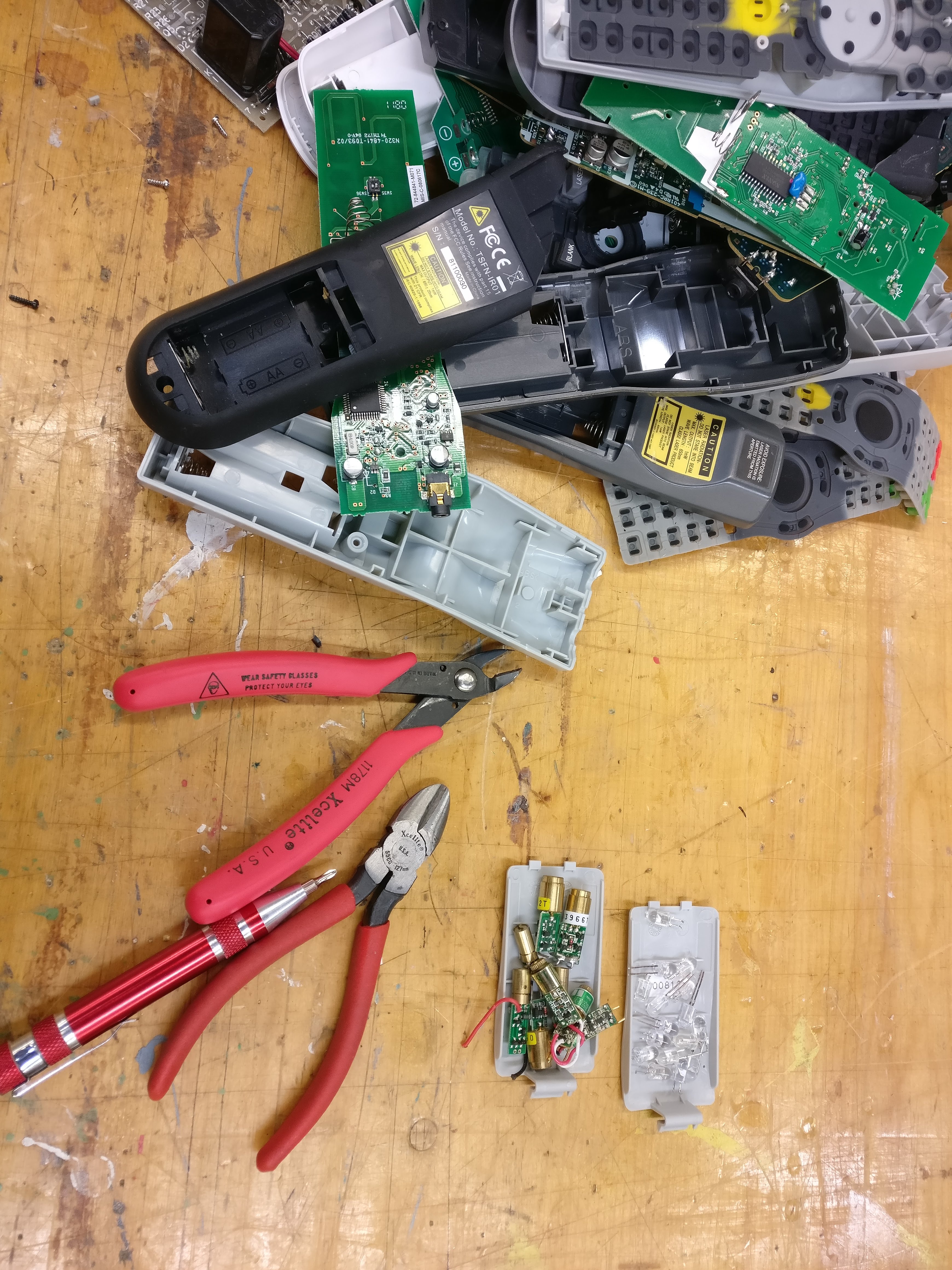

Building the frame and lasers

I didn’t have a lot of time to make the first version, so I tried to find a cheap source for the lasers; I bought a dozen cheap laser pointers to use. Unfortunately, these proved to be next to useless for what I was planning. They weren’t easily altered, plus the lasers were weak and the beams weren’t focused. In the end, I went through my box of old remotes. My work as an Electronics Technologist has me taking care of a lot of TVs and projectors, and projector remotes often have a red laser built into them. So after an hour or so of scrounging and busting open old remotes, I had enough for one full octave of “strings.”

Mounting the “strings”

I mounted each laser in the top of the acrylic frame by hand, and hot glued them into place. Hot glue is a great material if you aren’t completely sure if you will need to change it afterwards, because if you just add a little heat you can make changes or even completely remove it. I aimed the lasers at light dependent resistors (LDRs) — electronic components that are sensitive to light — located in the base of the harp.

At this stage, I encountered a problem: Even after hand aiming the lasers, I found that with movement and changes in the room lighting, the harp wouldn’t work correctly. To solve this, I potted each LDR in hot glue, to act like a large diffuser. To do so, I placed a ring around each LDR, and filled it with a few millimeters of hot glue. This made sure that the light was even and consistent, even if the lasers moved slightly.

The circuitry of the harp is simple enough; it relies on a LDR being in the path of the laser, which saturates the LDR. So when something (like your hand) blocks the laser beam, the absence can be detected. Each of the strings is connected to a microcontroller, which is programmed to detect the changes in the light and then to produce a MIDI note. This is then sent to the computer, some MIDI software interprets it, and a note is played on the speakers.

A new challenge

The Symphony Hack Lab event went well, and the audience enjoyed playing with the harp. Afterwards I was asked if I could make a second harp that could be more portable, and that wouldn’t need a laptop to create sound.

Stay tuned for Jonathan’s next article, Music meets technology: Raising the bar, where he explains how he created Version 2 — a fully portable laser harp.

Enjoying the Ingenium Channel? Help us improve your experience with a short survey!