Industrial Transfers and the Art of Decalcomania: Collection Profile

Industrial transfers were a form of decal commonly used in Canada, and around the world, replacing the expensive method of hand painting coats of arms, trademarks, signs, ornaments, letters and numbers on railway equipment, ships and industrial machinery.

INTRODUCTION

The Canada Science and Technology Museum possesses a rich and comprehensive collection of late nineteenth and early twentieth century industrial transfers. Industrial transfers were a form of decal commonly used in Canada, and around the world, replacing the expensive method of hand painting coats of arms, trademarks, signs, ornaments, letters and numbers on railway equipment, ships and industrial machinery.

"Who has not admired an American railway train, when cars and engine are newly painted and decorated? Who does not look with preference at an omnibus, when finely decorated, and placed along side of one which has only the streets painted on it in large red letters?”

The American Painter and Decorator, March 1876

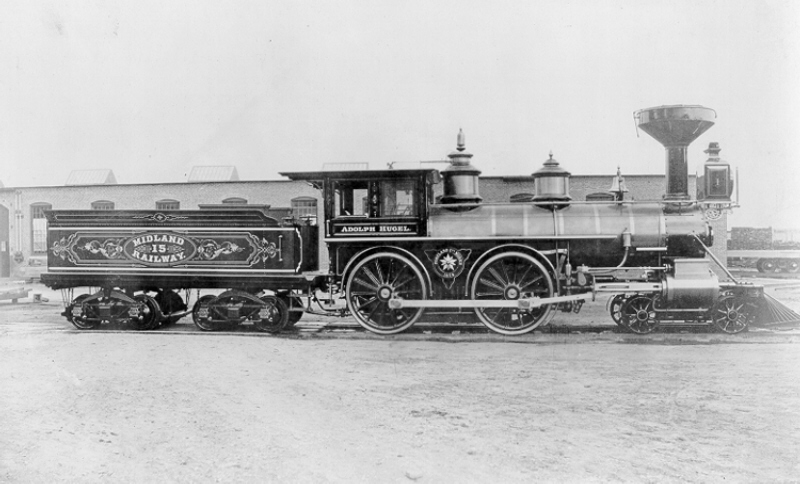

A beautifully decorated Midland Railway of Canada steam locomotive, No. 15 “Adolph Hugel” type 4-4-0, ca 1880

The backing of a decal can reveal the application technique, in this case a duplex method, which allowed the separation of the paper after the image was firmly placed on the surface.

Properly affixed, transfers were highly durable, making them an especially desirable form of lettering and decoration on equipment exposed to various climatic conditions, such as rail stock running in extreme tropical or dry climates, and extensively used with limited maintenance on long distance routes.

The Museum’s collection has a unique historical and educational value. Even though the word “transfer,” or its American equivalent, “decalcomania,” was often used to describe a drawing, design, or pattern that could be moved from one surface to another through direct contact, and the decorative technique itself was well known, both terms were usually associated with chinaware and pottery decoration. Yet industrial transfers, applied for example to railway stock or commercial vehicles, were not as common. In this regard the collection is a valuable resource, allowing for the analyses of printmaking techniques of the late nineteenth century, such as the lithographic process, as well as studies of industrial object design and the early graphic arts.

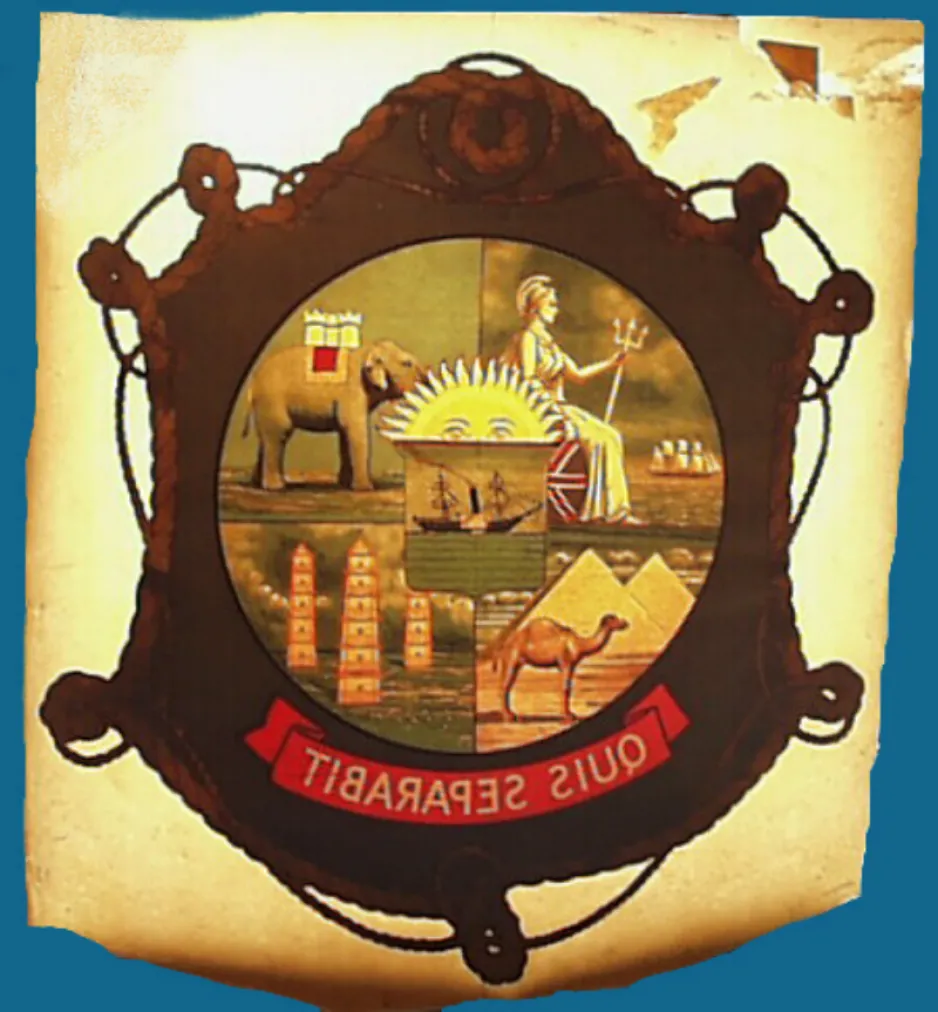

The coat of arms of the Buenos Aires Central South Railway Company, Tearne & Sons

THE COLLECTION

The Museum has been acquiring transfers since its founding. However, the collection has been significantly enriched by two donations made in 1975 and 2000, consisting of transfers collected by

Roger Sylvester and by Andrew Merrilees.

At present, the Museum holds over 1 500 original designs and, since in many cases there are several copies of the same image, almost 17 000 individual decals, produced between the late 1880s and early 1960s. The many duplications in the collection allow for true preservation of one copy, while others may be transferred for display as finished products, or studied for research purposes. For example, the analysis of the paper used to produce a decal can only be performed on the artifact prior to transfer.

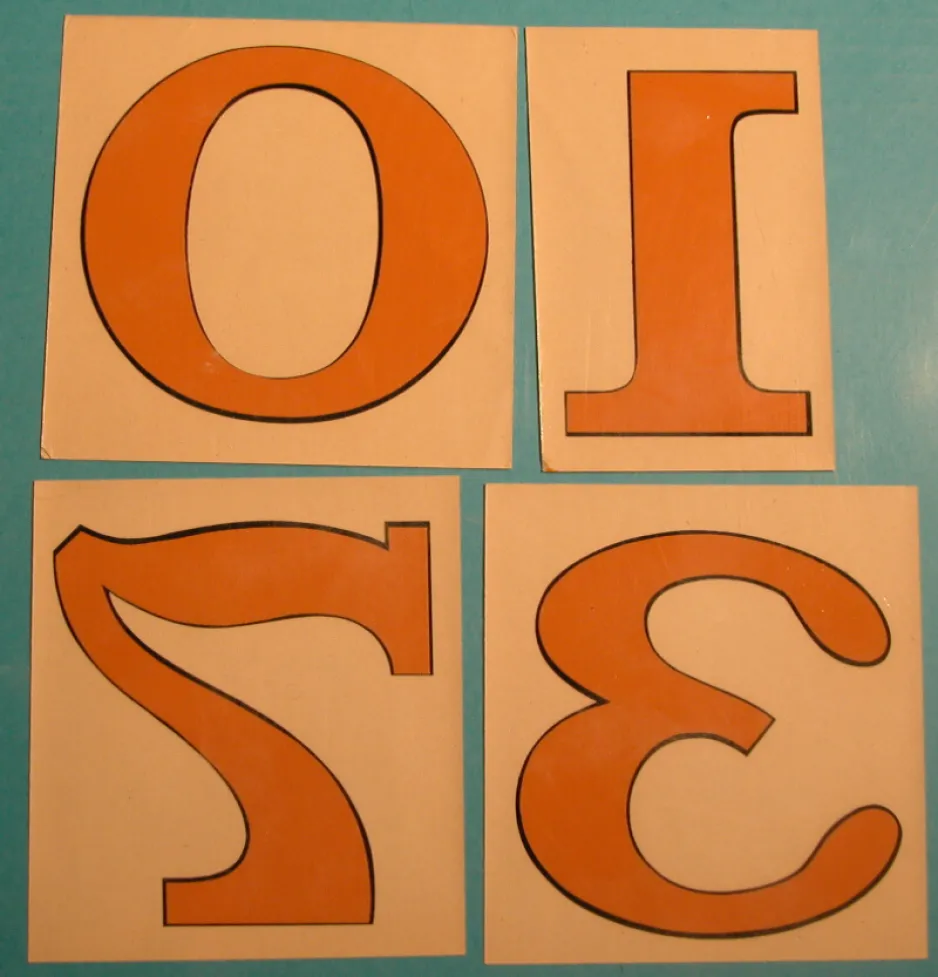

Letters and numbers produced by the Canada Decalcomania Company for the Canadian National Railway.

Among the most interesting items are nineteenth-century coats of arms produced by a British transfer maker, Tearne & Sons; handmade patterns for letters and numbers used by colonial railways; and, signs and trademarks produced by the Canada Decalcomania Company for the Canadian National Railway, Toronto Transportation Commission, Consumers Gas and other Canadian companies. They represent the vanishing phase of decorative arts that originated in Victorian extrinsic ornamentation and carried on well into the first decades of the twentieth century. As the styles of industrial embellishment changed the role of the artist-craftsman became obsolete and, even as factors such as the range of colours that were commercially accessible increased, the transfers became a testimony to the past philosophy and techniques of decorative arts.

By 1890, sewing machines were commonly decorated with gold leaf and transfers.

ORIGINS OF TRANSFER ORNAMENTATION

The origin of transfer design is not certain. One debatable story, first recorded in 1871, suggests that John Sadler conceived the idea of decorating pottery with printed images while watching a group of children decorating their doll houses. Indeed, John Sadler and Guy Green—both well-known printers and engravers working in Liverpool—claimed to have invented the technique in 1756 to decorate pottery for the famous Josiah Wedgewood. This claim, however, is contested by evidence that in 1751 and 1755, John Brooks, an engraver employed by Battersea Enamel Works, attempted to patent the monochrome transfer technique, which involved etching and inking an image onto a copper plate and then imprinting it onto a wet paper, which in turn was pressed against a piece of pottery, leaving an impression.

A clock made by the Arthur Pequegnat Clock Company, ca 1904, decorated with a transfer image of King Edward VII

But even if Sadler and Green did not invent transfers, they perfected the engraving process and printing techniques and inaugurated an underglaze printing, which by the 1770s brought the price of pottery decoration from £2 per piece to 6 pence. The technique spread from England to Sweden, Germany, France and to North America.

In Germany, the transfers were used to imitate gold leaf on iron sewing machines and wooden clocks, and soon they were applied to household appliances, coaches, railway cars and industrial machinery around the world. By 1890, decalcomania had become one of the most common methods of ornamentation of technological artifacts.

Transfers offered an inexpensive method of decorating household items such as this nineteenth-century cylinder player.

Canadians first ventured into industrial transfer technology in 1871, when Henry McElcheran, a painter from Hamilton, Ontario, searched for a new way to decorate coaches. During his experiments, he combined glue, sugar, glycerine and balsam of fir, creating a perfectly pliable sheet of material, which could be easily imprinted by wood cuts, and could adhere to any surface. Yet, in the nineteenth century, the Canadian market was generally dominated by imported British and American products. This situation persisted until 1911 when the Canada Decalcomania Company opened an office in Toronto and soon produced decals for many Canadian companies. Unfortunately, the transfers in their original paper form were very fragile and, unless properly stored, rarely survived more than a few years. Today, decals produced by Canada Decalcomania are very rare.

Samuel Tearne advertisement

TEARNE & SONS

Most transfers that exist today, in their original form, owe their survival to the keen eye of a collector. In the 1960s, for example, the British company Tearne & Sons was melting old decals to recover the gold and silver used in their production. Fortunately two Canadian collectors, Roger Sylvester and Andrew Merrilees, managed to purchase the remaining stock from Tearne before all the transfers were destroyed. They brought the decals to Canada where they were later acquired by the Canada Science and Technology Museum.

Tearne & Sons, whose transfers now constitute the majority of the decals preserved by the Museum, was established by Samuel Tearne in 1856. Located in the famous Birmingham jewellery quarter, it mainly manufactured jewellery boxes.

With this experience in decorative arts, and an interest in the newest technologies, the company started producing transfers for bicycles in the 1870s and by the end of the decade was the main manufacturer of railway transfer art in Great Britain, supplying decals to many major transportation companies worldwide, as well as municipalities and counties, the Royal Household, the British Armed Forces and the Royal Air Force. The company is still in existence, producing transfers for the famous Orient Express.

Instructions for the coat of arms of the Lancaster Company from Buenos Aires disclose handwritten descriptions of colours (“shaded gray and green”, “gold”, “green line”), and dated approvals of changes to the master design.

PRODUCTION OF TRANSFERS

The chromolithographic transfer technique used to produce most of the decals in the Museum’s collection facilitated the reproduction of the multicolour decorations, lettering and numbers on any surface including glass, metal or wood, offering a less expensive alternative to hand painting and brushwork.

The process of preparing transfers, though less expensive than the alternatives, was nevertheless quite complicated and required artistic skills and knowledge of printing techniques. First, the customer provided a master copy of the image to be reproduced. This copy usually included a detailed description of the design, size and colour dyes. Transfer manufacturers were allowed very little creative change to the master design, especially in the case of the coats of arms approved by the College of Heraldry. In some cases, however, artistic expression had to be compromised with function — the process of transferring imposed limitations on design and some elements of an image had to be simplified. After the master image was finalized, it was given to an artist-craftsman who was responsible for engraving it onto lithographic stones.

A rare coat of arms of the P & O Company; the extensive design and the blend of colours and shades was expensive to reproduce and difficult to transfer, and the arms were quickly abandoned by the company.

The image was first reproduced on a “key stone” that was not used for printing itself, but rather served as an outline, a lithographic “master copy,” for other imprints. Next the artist made one engraving for each colour used in the design. The colours and shades used on the image were carefully examined in order to prepare matching dyes. The image from a key stone was then impressed upon lithographic stones, producing as many duplicate plates as were required to print the colour image. Each area that required a different colour was engraved on a separate stone. The colour was inked in and preserved with a thin layer of gum arabic.

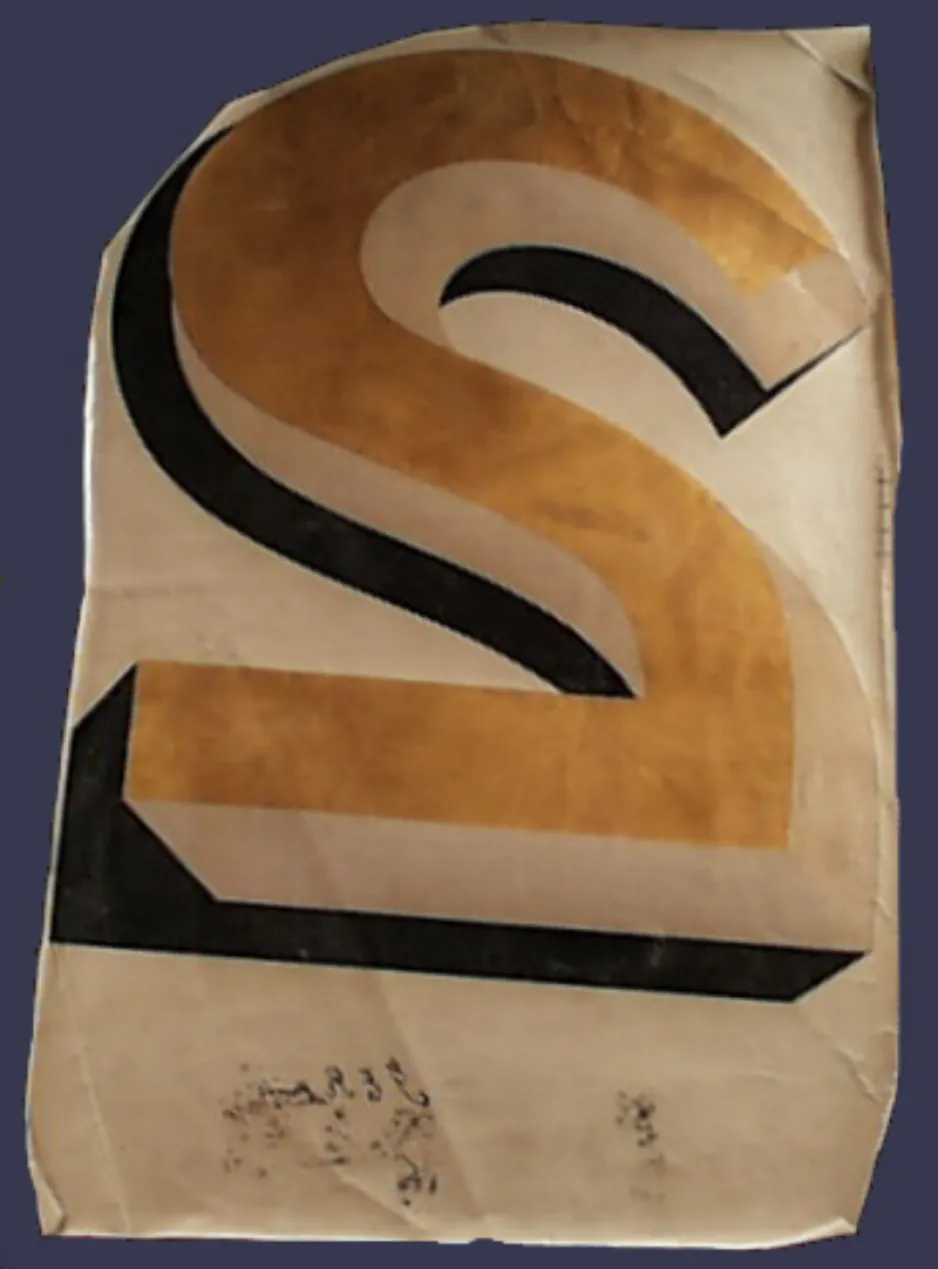

Proof of the number 2 prepared by Tearne & Sons for the Great Eastern Railway

The application of the dyes followed a specific order of the transparent colours first and opaque last, which is the reverse of standard painting. The colour plates were then given to a pressman, who proceeded with the process of lithographic printing. The first imprint, done on an inexpensive paper, was called a proof; it was inspected for errors, colours were matched against the original design, and any alternations or directions were handwritten and signed by the lithographer.

The letters FCT, a monogram of the Taltal Railway Company, produced in reverse in order to transfer right side up

The creation of transfers required a high degree of skill. The image was impressed on the paper in reverse, in order for it to transfer right side up on the surface. Every stone had to be carefully aligned to complement perfectly succeeding colours, and with each added dye the face of the image was less visible to the pressman, making the process very time-consuming. The parts of the design that were to be filled with pure gold or silver were left empty until all the other colours were ready, at which point a coat of liquid metal was applied over the entire design.

Tearne & Sons transfers coated with gold leaf

The transfer paper was very sensitive to environmental changes, expanding and shrinking with even slight variations in temperature and humidity, making it impossible to align the colours and complete the decal. As a result, many transfer shops were equipped with environmental control units. In fact, the Palm Brothers Decalcomania Company plant in Norwood, Ohio, was the earliest air conditioned building in the state.

The preparation of the decal paper was the most expensive part of the transfer making. Decal paper, classified as gummed paper, was not manufactured in mills but was prepared by transfer makers themselves or converters, also called coaters, who specialized in finish applications. One of the better-known coaters was Tullis Russell Brittains, a company that supplied paper to Tearne & Sons in England and Commercial Decal Incorporated in the United States.

An image of the Bombay, Baroda & Central India Railway coat of arms printed directly onto a simplex paper; a single layer made the process of transferring difficult and the paper was later replaced by a duplex paper, which was easily separated from the image.

There were two categories of decal paper: an older type “simplex,” or “single paper” that consisted of a single layer of a heavy water-penetrable paper sheet, and newer “duplex,” or “double paper,” made up of a non-porous paper and a thin tissue attached to it semi-permanently. The final image imprinted on both types of paper looked identical, and the two could be told apart only by carefully examining the edges of the transfer paper. The edge of the simplex was smooth, but the duplex often revealed the thin tissue separating the backings.

The surface of the transfer paper was coated with three layers. An undercoat was made of a starch filling evenly applied over the surface. When this coat was dry, the sheets of paper were polished between hot rollers. Then came a coat of glycerine that made the sheet pliant and prevented fractures in the starched surface. The last layer, called a transfer surface, consisted of starch, albumen and a solution of gum arabic. The sheets were then stored at a constant temperature, and allowed to season between each layer for up to thirty days. These special coats allowed the image to separate easily from the paper when transferred.

A transferred monogram placed on the Royal Train during the 1939 Royal Tour of Canada

TRANSFERRING TECHNIQUES

Three different techniques were used to apply decals: water release, cement mounting, or a pressure sensitive process, used mostly for porcelain decoration.

The water-released decals were the most common type, and were divided into three subtypes: the water slide-off type — as implied by the name, the image was printed right side up and slid off the paper onto a surface face up; direct transfers, which required a light coat of varnish to be applied over the image and then placed in direct contact with the receiving surface; and, double purpose transfers, usually applied on glass and read from either side. The water-released direct transfers were printed on simplex paper. Originally, the entire decal was saturated before transfer. When the decal was placed in water, the mixture of gelatine, albumen and gum arabic separated from the paper and floated on the water. The decal was carefully lifted, pressed on the transferring surface and left to dry. The transferred image was always covered with lacquer or varnish to enhance its durability.

Because the image could easily be damaged when lifted from the water, a safer technique was eventually developed. First the transferring surface was cleaned of dust and dirt. Then the surface of the image was painted with a thin coat of varnish and left to dry. Just before transferring, the image was painted with another layer of varnish and the entire transfer, including the backing sheet, was pressed onto a surface, from the centre toward the edges. When the decal was firmly attached to the surface, the paper layer was slowly saturated with water. This process required precision in order to prevent the water from soaking through to the image layer. The soaked backing paper was then detached from the design.

A duplex transfer with the monogram of King George VI

The water-released transfers prepared on the duplex paper required a cement mounting technique. A small area of tissue, usually at the corner, was first separated from the backing paper. The image was then coated with decal cement applied with a soft cloth and left to set for about ten minutes. When the cement reached a very specific thickness, the decal was pressed to a clean wet surface and rolled down with a rubber roller or sponge. The wet surface prevented the decal from attaching immediately and made it easier to position the transfer.

The backing paper was peeled away starting with the loose corner. The tissue paper and some gum arabic deposit would remain on the design and had to be removed with a wet sponge. If these remnants were allowed to dry, they would crack the transfer, damaging the image. The affixed transfer was allowed to dry for up to two weeks before being washed with benzine to remove surplus cement. The final image was protected with a coat of varnish.

A china set used at the Chateau Laurier was decorated with transfers depicting the Canadian National Railway logo.

EACH ONE IDENTIFIES A PRODUCT

“Each one of these Canada Decalcomania Transfers identifies a product. You simply dip them in water and slide them off the paper onto the article” — so Canada Decalcomania promoted its merchandise in 1931.

Indeed, the transfers not only adorned common objects, but also expressed and reinforced among customers the corporate identity of the company. These corporate coats of arms, monograms and trademarks constitute the most artistically interesting part of the transfer collection. In the nineteenth century it was customary for institutions to have a coat of arms. Railway companies, for example, acquired a heraldic design when they incorporated, as a seal for legal documents.

The coat of arms of the Great Western Railway

Designs were assembled from the designs of the towns they served, or simply by placing the company’s name in a garter. The coats of arms in the Museum’s transfer collection include, among others, arms of the Great Southern Railway, Great Western Railway, North Western Railway, Barranquilla Railway & Pier Company, East Indian Railways, Egyptian State Railway, and Kenya & Uganda Railway, royal coats of arms and monograms, and numerous devices of cities that were placed on public transportation.

A decal made by the Canada Decalcomania Company for Pierre Thibault Canada Ltée, a manufacturer of fire trucks.

The collection also includes examples of images made for shipping companies as well as trademarks of businesses and manufacturers. Among the most interesting trademarks are the images designed by Canada Decalcomania for Pierre Thibault, and placed on fire trucks produced by his company; ACME Decalcomania’s decals for the Canadian Fire Chiefs Association; and, transfers made by Tearnes for Wagon Repairers Limited; Pinckering Stock; Robey & Company; Marshall, Sons & Company; and, Huntley and Palmer to name a few.

The image of a galloping horse on a deep gold background, made by Tearne & Sons for John Marston & Company, reveals the skill of the Tearne craftsmen, but also reflects Victorian taste for exaggerated ornamentation.

Some of these companies used a simple design that implied an association with a product, but most examples included in the collection show a heavy armorial influence and manufacturers’ preoccupation with the overly ornamental designs that dominated Victorian times and apparently were still very popular in the first decades of the twentieth century.

A face of a woman designated the “Ladies Only” railway cars.

The industrial transfers blended aesthetics and utility. Signage for wayfinding and warnings was designed in simple lettering, but was enriched by colours and shadings. Some notices for colonial railways, for example, Central India Railways, were printed in three languages: English and two local dialects. Images that often replaced signs, such as a face of a woman designating “ladies only” compartments, were nothing but schematic; their design was elaborate, and colourful, and it was obvious that the artistic value of these transfers was, in some cases, more important to railway companies than the price of decals.

A highly decorated sleeper car, ca 1890

Railway companies also devoted much attention to enhancing the interiors of rail cars, and the collection contains many examples of silver and gold interior decorative ornamentation: borders, corners, crowns and monograms, all intended to adorn the first-class cars.

A crest made by Tearne & Sons for the SS Yoma, 1928

Many decals from the Museum’s collection evoke interesting stories associated with the clients who ordered the art work. A good example is a simple crest produced for the SS Yoma in May 1928, as the ship was being built by W. Denny & Brothers. The ship was owned by the British & Burmese Company and operated as a part of the Henderson Line servicing the route from Glasgow to Rangoon. During the Second World War, the Yoma served as a troopship in the Mediterranean and was part of a convoy when she was sunk on June 17, 1943, by a U-81 near Derna. Out of 1 670 on board, 389 crew members were saved by marines from HMAS Lismore, many of whom dived into the sea to help their colleagues.

A bull’s head made for Wagon Repairers Limited in 1938 and used on the company’s vehicles

RARE AND UNIQUE COLLECTION

Although there are similar collections, both private and public, in Great Britain, the most notable at the National Railway Museum, the Canada Science and Technology Museum’s collection, with its emphasis on railway decals and company coats of arms, is unique in the North American context. Other Canadian museum transfer collections are rather small and consist mostly of decals already affixed onto another object.

Two major public decal collections are located in the United States. The Commercial Decal collection, donated to the Smithsonian Institution in 1993 by Charles Seliger, vice-president and artist/designer for the company, is preserved at the Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum in New York and the National Museum of American History Archives Center in Washington. The Commercial Decal collection is closely associated with the decorative arts, especially pottery and china ornamentation.

The company produced ceramic decals using mostly the screen technique — a process of projecting artwork onto a screen of silk, polyester, or woven wire cloth, coated with a photosensitive emulsion. It supplied companies such as Ridgewood Fine China, Haviland, Homer Laughlin, Corning and Medalta (Alberta). The other large collection of transfers preserved in North America consists of the archival documents of the Palm Brothers Decalcomania Company, the oldest American transfer producer, first incorporated in 1868. It is kept at the Cincinnati Museum Center. This very rich collection — half a cubic metre — contains correspondence, business and financial statements, sample decals as well as information on the company’s customers and the competition. The Palm Brothers produced decorative decals for a vast range of manufacturers: Ford Motor Company, Edison Phonograph Company, McLaughlin Carriage Company, and the Lakefield Canoe Building and Manufacturing Company, to name a few. Nonetheless, in the context of the study of the history of industrial arts and graphic design as an expression of corporate identity, the Canada Science and Technology Museum’s collection of transfers remains a rare and important resource.