Enhanced Reading: John Horn’s Volume of The Telegraph in America, 1879

Books are tools that organize knowledge. When readers access that knowledge, they engage a reading experience.

As part of that experience, some readers alter, enhance, and add onto a book’s text and pages. This can be in the form of marginalia, where a reader marks the page with critiques, annotations, or even scribbles and doodles. Another practice is when a book’s owner inserts extra illustrations to supplement the text. The resulting composite volume is what book historians and collectors refer to as grangerized. The practice of grangerizing has elements of scrapbooking, but it is marked by enhancing an existing book. In some especially involved cases, book owners would dismantle a book, make inclusions that greatly expanded its size, and reconstruct it as a unique and personal volume. Both practices can help reveal what a reader thought about a particular book and how they used it as a resource.

Whether marks on a page, commentary on a text, or material additions, enhanced reading experiences are extraordinary. They augment the book and communicate ideas and information that the original and unmodified version cannot. Ingenium: Canada’s Museums of Science and Innovation holds a fine example of a book enriched by its owner: The Telegraph in America: Its founders, promoters, and noted men.

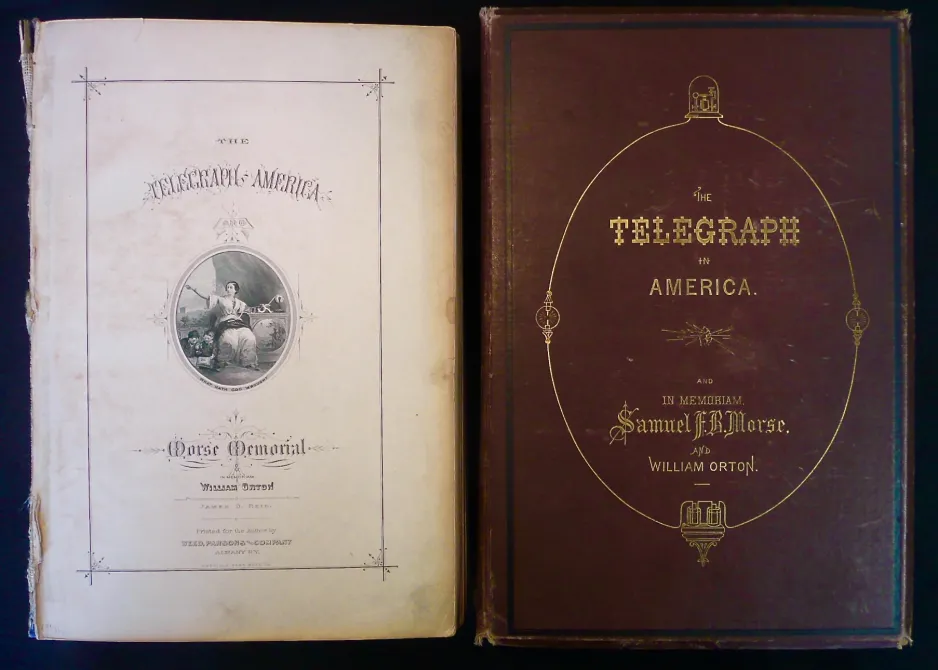

Cover and title page of John Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America. The book is in fair condition. The cover, however, was dislocated from the book before it arrived at Canada Science and Technology Museum.

The volume belonged to a Canadian telegraph operator named John Horn. He added a range of materials relating to the people and events discussed in the book. In doing so, he effectively inserts himself into the telegraph’s story. Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America is important because it helps document a reading experience – something which is extremely difficult to capture.

The book’s author, James D. Reid, worked for the Magnetic Telegraph Company and his book owes its origins to a ceremony that celebrated Samuel Morse, the telegraph pioneer, in New York’s Central Park in June 1871. Participants at the ceremony noted that the telegraph’s growth in America was so swift and recent that no one had yet written a history of its development. Reid’s book has two purposes. It preserves the celebration and speeches made in Morse’s honour and historicizes the telegraph’s development in Canada and the United States.

The Telegraph in America was published in New York by Derby Brothers in 1879 and it is full of technical illustrations and 45 portrait engravings. On its own, it is an imposing resource at 846 pages. It is organized into three sections. Part one is a history of The Telegraph in America and Samuel Morse’s significance to its success. Part two gives a summary of 39 telegraph companies, including for each one a brief history of the company’s development, connections, rates, operators, and owners. In part three, Reid provides an account of the June 1871 ceremony and the various commemorations made with Morse’s death in 1872. Included in this section is a memorial to William Orton, who served as president of the Western Union Telegraph Company and died in 1878. As Reid put it, the book is meant as a testimony to how Morse “had placed the telegraph in America high among the great industries of the world.”

John Horn, the original owner of the volume of The Telegraph in America at Ingenium, had a lively career as a telegraphist. Born in 1837 in Montreal, he began work with the Montreal Telegraph Company in 1853 and eventually gained charge of their New York connection. In 1857 he moved to New York and worked for the American Telegraph Company and then the Western Union Telegraph Company where he managed their stock exchange business. It is unclear when, but Horn eventually returned to Canada in the early 1880s. In 1884, he edited Canada’s first electrical journal, Canadian Electric News, published in Montreal by Hart Bros. & Co. In 1885, Horn volunteered for the 9th Battalion of Quebec (Les Voltigeurs de Québec) to assist with field operations for the Canadian Military Telegraph Service in the North West Rebellion. He returned to Montreal by 1886, and receiving patronage from businessman and philanthropist Lord Strathcona, worked as an amateur historian of Montreal.

Program for the Morse Memorial in Central Park, 1871. The program appears between pages 718-19 in Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America. On page 719, Horn has also added his name to a list of people who took part in a riverboat cruise as part of the celebration.

John Horn filled his copy of The Telegraph in America with all sorts of additional materials including personal recollections, correspondence, envelopes, newspaper clippings, telegrams, and photographs. He even included the program for Morse’s 1871 commemoration and an invitation to the private reception that followed. In some cases, the supplementary material is glued into the book and in others, the additions are loose and tucked between the pages. Annotations in the book are also thrilling. Horn corrects typographical errors and adds information and details informed by his own experience with the world of telegraphy. As an object, the book is more than just a copy of The Telegraph in America. The inscribed and material additions offer insight into how this reader used the book as a resource. John Horn was a dedicated collector of all sorts of materials associated with telegraphy. Ingenium also holds a sizeable scrapbook made by Horn. It is filled with letters, portraits, and ephemera related to Samuel Morse and the telegraph’s early history in the United States and Canada.

John Horn’s scrapbook is over 200 pages filled with correspondence, telegrams, newspaper clippings, photographs, handwritten notes, extracts from books, and ephemera all about and relating to Samuel Morse and telegraphic communications more broadly.

John Horn did not make the insertions at random. He supplemented the text in very specific ways. While it is not clear if someone has shuffled around the unattached papers, in their present state, most of them offer auxiliary information to enrich the reading experience of the pages between which they appear. Nearly all of the papers have a number written in pencil in one of the top corners, which indicates that Horn meant for his additions to have order. When the book mentions a particular person, and Horn provided extra information, he often underlined the associated name in a blue editor’s pencil. Fittingly, it is reminiscent of a hyperlink – the reader is meant to jump over to whatever inclusions the creative reader inserted to augment the reading experience. There are at least 144 items added to Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America.

Page 71 of Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America shows the names Francis Ronalds and H. C. Oersted underlined in a blue editor’s pencil. Portraits of the men are clipped from periodicals and mounted on paper with their names and dates in pencil.

For example, a portrait of the scientist James Freeman Dana is included where the book explains his contributions to telegraphic technology. On the portrait’s reverse, Horn scrawled, “copied especially for me, at my expense.” In another case, when the book mentions Benjamin Franklin, Horn includes a letter from the Franklin Institute of Pennsylvania that acknowledges a donation to their library. When the book notes a trip that Samuel Morse took from Havre to New York in 1832, John Horn includes an envelope from the captain of the ship on which Morse sailed. On the envelope’s reverse he wrote, “The writing of Cap’t W. W. Pell of the ‘Sully’.” A funeral card for the inventor Harrison Gray Dyar has a personal note glued into the front, signed and dated by Horn, detailing his own memory and encounters with him. One of the 45 engravings included in the book is of William Corcoran, a Washington banker and telegraph financier. To make his copy superior, Horn includes a paper with Corcoran’s original signature, dated with the personal message, “Mr. John Horn with the regards of W. W. Corcoran.” The supplementary materials are detailed and varied.

Page 38 of Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America shows Captain Pell underlined in a blue editor’s pencil. Glued between pages 38-39 is a trimmed envelope with John Horn’s address. The reverse notes that the paper showcases the handwriting of Captain W. W. Pell.

Among the more sizeable inclusions is a 10-page handwritten copy of a speech made by William Cullen Bryant, editor of the New York Evening Post, when he revealed a bronze statue of Morse at the 1871 Central Park celebration. Horn also included a portrait of Bryant clipped from a magazine. As Horn’s volume has other copies of speeches made by dignitaries and telegrams received at the memorial, it is likely that this copy was written by Bryant and recited from in 1871. The address does not appear in the published version of The Telegraph in America.

Between pages 680-81 is a copy of the speech made by William Cullen Bryant, editor of the New York Evening Post, at the Morse Memorial in 1871. A portrait of Bryant, clipped from a magazine, is also included.

The most striking inclusions are ones that directly insert John Horn into the world of telegraphy more fully than he is credited in the book’s published form. The material insertions place Horn alongside the people historicized in the book. For example, the section that describes Morse’s memorial in New York includes an image of Morse sitting at a table with a telegraph, surrounded by people, with three vases filled with flowers placed in the foreground. In pencil, John Horn added the names of the people pictured, including himself, and records that it was he who placed the three flower vases in front of the table. It is an inconsequential detail, but one that establishes his presence at an important moment, helping to shape the scene. While the book also includes a printed sample of Morse’s handwriting, Horn incorporates a second example – the envelope from a letter Morse wrote to him 1871. On the reverse he notes, “The writing of Prof. Samuel F. B. Morse Inventor of the Electric Telegraph”.

At left, on page 740 of Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America, seven names are listed naming the people whom appear in the engraving: Applebaugh, Field, Morse, Morgan, Orton, Cronwell, Horn. Below, Horn wrote, “I placed the 3 vases of flowers” followed by his signature. At right, is the envelope addressed to John Horn from Samuel Morse in 1871.

Some items appear out of place. For example, a portrait of a man named T. C. Elwood. It is numbered 63 and placed between the front endpapers. It was likely meant to appear on page 341 where he is listed as a Divisional Superintendent for the Dominion Telegraph Company in Toronto. A possible reason for this is who the book passed to after John Horn. On the front flyleaf there is an ownership signature for Elwood Bigelow Hosmer, dated 1893. Elwood Hosmer was the son of prominent Montreal resident Charles Hosmer, who started work as a telegraphist at Grand Trunk Railway Telegraph before becoming the General Manager of Canadian Pacific Telegraph in 1880. In the 1870s, however, Charles Hosmer worked with T. C. Elwood as a Divisional Superintendent for the Dominion Telegraph Company. Moreover, both names are marked by a pencil on page 341. It is possible (though impossible to verify) that the portrait was removed from its place as Elwood Hosmer shared the book and the photograph with his father. What is more, item number 62 is absent from the book. It is possible (but again speculation) that the missing item was a portrait of Charles Hosmer, removed from the book, and repurposed by his son. With John Horn and Charles Hosmer being both from Montreal and the book passing to Charles Hosmer’s son, at the very least the book’s provenance gestures towards a fraternity and network among telegraph operators.

A portrait of T. C. Elwood, taken at Gragen & Fraser in Toronto, dated January 1886 on reverse. At top right, the ownership signature of Elwood B. Hosmer, 1893. At bottom right, a postcard dated 8/20/74 to John Horn from James D. Reid, author of The Telegraph in America. The card reads, “Well, busy, but nothing. Weather kul.”

The fact that Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America passed to a new owner well before his death in 1926 suggests that he meant for these material additions to be used and referenced by other readers. Remarkably, there are a few unnumbered items that may have been inserted by Elwood Hosmer – letters addressed to his father. While the extra illustration and textual inclusions were started and overwhelmingly carried out by Horn, Hosmer must have continued to fill the pages with additional pieces he believed relevant to supplement the book’s text.

John Horn’s volume of The Telegraph in America is part history of the telegraph and part history of his life and personal interactions in the world of telegraphy. Though the book mentions his name only once in passing (that he contributed to organizing the 1871 event to celebrate Morse) Horn’s version of history situates himself in a network with prominent people in the telegraph industry and implies he played an essential part of the history of the telegraph in America.